By: Peter Jančič (Spletni časopis)

The surprise of the week was not that Marko Crnkovič, in Večer and other media owned by Martin Odlazek, attacked Lija Zuljan, the daughter of Šank Rock guitarist Boro Zuljan, for posting this message to her father on Facebook: “You lie, you cheat on my mom with the president of the National Assembly…”

That it leaked to the public that Urška Klakočar Zupančič is not only paying Zuljan for playing guitar at the Statehood Day celebration was embarrassing, and someone had to be blamed. Crnkovič found his culprit in the daughter.

The only thing missing was for Crnkovič to take his hypothesis to the end and claim that Zuljan raised her poorly, which is why she is now causing such trouble for the president of the parliament. She should have kept quiet. This is about the state, not her family.

A more common culprit was found by Necenzurirano’s Primož Cirman, who declared that the members of the SDS party and media affiliated with it were the source of the problem.

Cirman and his team, as always, declared that SDS was to blame for everything, stating:

“Who filed a criminal complaint against Urška Klakočar Zupančič? A “civil initiative” led by an SDS member.

The President of the National Assembly, Urška Klakočar Zupančič, has recently become a main target of portals connected to the SDS circle. Now, she has also been hit with a criminal complaint.

It was filed by a civil initiative behind which SDS members are hiding.”

If we ignore the reactions of these government-aligned media, which regularly monitor all opposition party members, the real surprise of the week was the statement that the public has no right to know the gross salary received by President of the Republic Nataša Pirc Musar. Such a response from the office of President Nataša Pirc Musar, which they stuck to even when I protested – wondering if they had lost their minds – came at a time when the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption was supposed to start granting public access to data on the gross salaries of all individuals in state institutions and companies that exceed the president’s gross salary. Which we are now not allowed to know. Because, apparently, it is now a private matter.

Last year, we could still find out. Things are changing fast.

That all recipients of state salaries exceeding the president’s salary should be disclosed in the Erar application was legislated in parliament during Marjan Šarec’s government. Janša is not to blame. A miracle. Yet, it still did not happen. A constitutional dispute against something that had not even happened was initiated by GEN-I. The Constitutional Court rejected GEN-I’s request for a temporary suspension of the reform and the upgrade of Erar.

But the data is not in Erar. At least, it is not visible. And at least some legal experts believe GEN-I is panicking unnecessarily because they do not actually have to disclose data on their astronomical salaries – since they are a private company fully owned by the state. A special Slovenian category. Above all, a monopoly reseller of electricity from the state’s nuclear plant. A highly lucrative business.

During the upgrade of Erar by the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption (CPC), we witnessed the influence of GEN-I. When the transaction database of state-owned companies showed a payment of ten million euros to a private individual (without name or surname), even though the money actually went to the Clearing and Depository Company for bond repayments, there was a major uproar in the media. GEN-I even threatened CPC with a lawsuit – despite the fact that CPC was not responsible for the incorrect data label. And such errors are nothing unusual. They are the norm, a method through which GEN-I and others conceal enormous payouts to individuals from the public. And when they do it themselves, it is not considered a mistake.

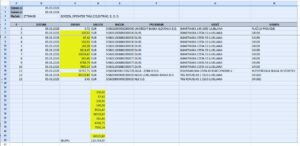

How they hide data as a snake hides its legs is evident in an example a reader pointed out to me – concerning the payment of an additional bonus of €3,094 to each of 40 employees at the state-owned company Borzen. They received this money as a reward for successfully distributing state funds for subsidies – including to the prime minister’s company, Star Solar. This payment is missing from the state transaction database (which Erar pulls data from). Instead, it was presented as a single transfer of €83,126 to NLB, along with an additional payment to the tax authority, totalling exactly €123,764. Like this:

The sum precisely matches Borzen director Mojca Kert’s statement that she would pay employees a bonus equivalent to an average salary.

The additional payments to all employees were not a payment to the legal entity NLB, as presented. The money went to employees. Individuals. Physical persons, as a bonus. It is the same type of misrepresented data that GEN-I threatened CPC with lawsuits over. But in this case, they remain silent as mice.

Because this is exactly what GEN-I feared – and why we witnessed the attack on CPC. They systematically conceal a massive number of payments to private individuals by presenting them as transfers to legal entities. To banks.

So that it would not become public how much former and current management teams – and others – have pocketed. The astronomical pension bonuses, of which only a small part will be subject to a referendum, ensuring up to €3,000 net lifelong pensions, are not the only unusual perk in this country.

We all remember that, due to media pressure, Prime Minister Robert Golob had to forgo an additional million-euro bonus for his success in reselling state electricity – after already receiving about a million euros more over four years than what was allowed under the Matej Lahovnik Law. This law was passed in parliament to curb excessive looting in state-owned enterprises. However, during Golob’s tenure, GEN-I was declared a non-state company, making these restrictions inapplicable.

It remains unclear whether all other former members of Golob’s management team also later renounced their astronomical bonuses. Journalists cannot verify this. The data is concealed – just like President Pirc Musar’s salary. The ruling coalition also blocked a parliamentary investigation into these matters, preventing the opposition SDS from scrutinising them. The NSi party helped by refusing to provide the necessary signatures for a parliamentary inquiry, which was then demanded by the State Council. This allowed Svoboda to take control of the investigation, which should have been led by the opposition. By taking over leadership, they once again blocked the inquiry.

The extent to which journalists can investigate was further demonstrated when I pointed out (again, based on tips from readers) that SDH had signed contracts with three detective agencies – almost simultaneously with hiring Damir Črnčec – each for more than a quarter of a million euros. The enormous sum and the timing suggested that intelligence officer Črnčec might have secured his own army of well-paid spies. In an election year.

When I asked SDH for clarification on this generosity and the contracts to determine what these detectives would actually be doing, they responded that the total amount allocated was a quarter of a million euros for all three agencies combined, not per agency. They even suggested that I should have checked this before publishing the story. A little later, they added an explanation that they had miswritten the contents of the contracts they were required to disclose – since each company was listed with a quarter-million-euro contract – and that they had now corrected the public records.

Can you imagine? The manager of state-owned enterprises, overseeing €10 billion, publicly announces that it has awarded three detective agencies €250,000 each, and a journalist is supposed to verify before publication whether they mistakenly disclosed this information incorrectly.

The explanation that this was a total amount misrepresented as separate payments is also suspicious. How exactly was this total sum divided among the three agencies in the individual contracts? Was there a single contract covering all three companies?

We cannot know the truth because they have not provided me with the contracts I requested.

And this is the kind of “verification” that they demand from the media. We cannot verify because the documents are hidden. Yet, they are furious at us for not verifying – something we cannot do. Well, I am still waiting. Maybe they will send the contracts after all. Now that the story is out, SDH’s oversight board and others with more access might finally take a look.

Journalists have very few options.

We cannot even present you with full salary data for Nataša Pirc Musar and Zoran Janković because the people are not entitled to know that much about their vanguard – their elected leaders.

Whether the Information Commissioner will order the disclosure of these “secrets” – just as she recently did with the list of privileged pension recipients and their heirs, which the government and ZPIZ tried to conceal – remains to be seen.