By: Gašper Blažič

Although Serbian “vožd” Slobodan Milosević has been dead for fifteen years, his secret cosy deals with Milan Kučan, the only surviving former president of one of the Yugoslav republics, are still influencing events.

It is generally known that Kučan’s area of interest after the disintegration of the SFRY was especially the Republika Srpska, i.e. one of the entities in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). During Pahor’s government (2008-2011), Kučan was even a kind of envoy for Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 2010, Pahor’s government appointed him a special envoy of the Prime Minister to determine the possibility of carrying out constitutional reforms in BiH in early November. In the autumn of that year, Kučan had several meetings with BiH leaders and submitted a report to the then Prime Minister Pahor, now President of the Republic. It is not known whether Kučan’s function was of an international nature or whether it was only a one-sided Slovenian move. However, Pahor said at the time that Kučan’s report was “very good”, while the media reported that Kučan had prepared a proposal based on the information obtained, “with which, according to Kučan, our country will participate in the discussion at the EU summit on the future of BiH.” They did not write about the details.

Did the European Union really propose Kučan?

Interestingly, Pahor announced the decision of his government to appoint Kučan as an envoy without explanation in early November 2010, saying that Kučan would tell himself why he had been appointed. The media accompanied this decision by stating that it was an appointment based on Kučan’s allegedly positive role in the attempt to peacefully break up the Yugoslav republics or the disintegration of Yugoslavia, in doing so Kučan was supposedly even proposed by the European Union, which he himself did not confirm. As is well known, in the six months between the Slovene plebiscite and Slovene independence, several meetings of six republican leaders took place on this very topic, but the meetings did not bring a solution. Representatives of the provinces and federal authorities did not participate in this.

It is also known that Kučan was recommended as a possible mediator among the representatives of the nations in BiH by the then Foreign Minister Samuel Žbogar. As if to say, Kučan has an added value, as representatives of various parties in BiH will be able to be more open with him, as he has a great reputation among all representatives of nations in BiH. The kind of work Kučan actually did there was never explained to the public.

Regardless of the fact that soon after the independence of Slovenia, the word about Kučan spread throughout Europe as the politician who most resolutely opposed Milošević in the Yugoslav context, there is also other information. In an interview with a Serbian media, Kučan even admitted that he was sorry for Milosević, saying that he was a pragmatic man who was addicted to power. Kučan also described his feelings when he participated as a witness in the Milošević trial in The Hague.

A relationship inspired by selfish interests

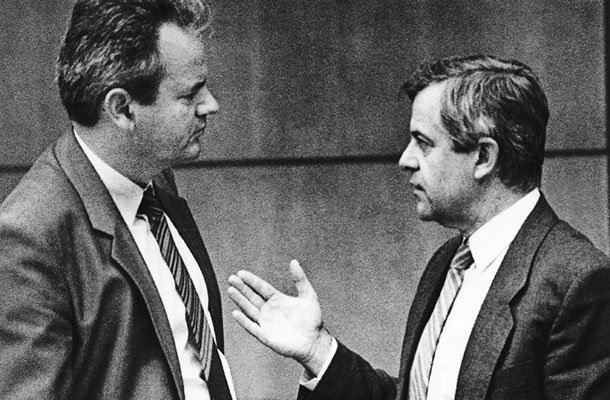

Of course, it is not possible to deduce from this interview what their relationship had been over the years, except that after that intervention in Kosovo Polje in April 1987, when he told the present crowd “No one should beat you”, it changed a lot and was never like it was before. And, of course, that they worked together for many years, as they were simultaneously, so to speak, elected president of both republican parties – Slovenia and Serbia. When the relations between Slovenia and Serbia tightened later, the Slovene communist leadership needed a conflict with Serbia, as it was aware that it needed a commitment to the nation, because the premonitions that the first multi-party elections were approaching were becoming clearer. The last major act of the ZKS, when its delegation left the last congress of the Yugoslav party, only confirmed this.

Of course, this does not mean that Kučan and Milošević were actually in conflict. Even more, they continued to maintain contacts, but more informally and away from the public eye, as this could harm them. It is no secret that Kučan was not in favour of Slovenia’s departure from Yugoslavia, and Milošević offered the public the option of “peaceful secession”, probably based on the model of amputation of “Little Croatia” from the late 1930s, which was prevented shortly before World War II by the Cvetković-Maček agreement. Such an option did not suit Kučan, for which there were both subjective and objective reasons. They were subjective in that the secession was not Kučan’s “intimate option” anyway, probably also because it would mean too much discontinuity for a political figure who perceived the SFRY as a programme that had to be implemented later in independent Slovenia. The objective reasons were that the international public would understand this as a unilateral secession, which would also mean the international isolation of (unrecognised) Slovenia, which would be left without any succession of the SFRY, also regarding the signing of international agreements, including the Osimo Agreements, which were very important for Slovenia regarding the relations with Italy.

What kind of pact did the party leaders from Slovenia and Serbia concluded?

Here, of course, the question arises again as to what pact did Milošević and Kučan concluded when Slovenia left Yugoslavia and what price Slovenia had to pay for it. Something is already known about the pact between Milošević and Croatian President Franjo Tuđman, including the fact that the pact wore off Croatia’s efforts to participate in a joint defence project (remember: Croatia remained passive during the YPA attack on Slovenia). It suited Milošević that by separate agreements he actually loosened the alliance between Slovenia and Croatia, as this made it easier for him to achieve his goal according to Plan B – that is Greater Serbia, in which Slovenia was no longer included, at least not in the short term.

The Hague trial also showed at what points Milosević and Kučan were real allies. Years ago, a rather extensive article about this was published by Janez Janša, who, among other things, wrote: “Kučan and Milosević agreed in advocating for the preservation of Yugoslavia. For both, this was the first goal. The historical recording of their meeting in December 1989 at the opening of the Belgrade branch of Studio Marketing has been a taboo topic on TV Slovenia for twenty years. Before that, they showed it a few times, and then never showed it again. Smiling faces and cheering with glasses is more than eloquent. Even more telling are the events that followed this meeting in the banking field. Shortly after this meeting, Ljubjana bank and Belgrade bank changed their units into branches in Yugoslavia, which until then had the status of independent banks with a guarantee from the then republics. With this, the parent bank (and consequently Slovenia in the case of LB) assumed all obligations to the savers of these branches. LB made this conversion despite the fact that the economic feasibility study advised against it to the management and supervisors. With this measure, which was carried out shortly after the Kučan-Milošević meeting only by Slovene and Serbian banks, they also wanted to connect Yugoslavia in commercial banking in such a way that the sentence – independence does not pay off for us – uttered countless times by the Slovene communists in those months in various versions, receive a material basis as well. Due to the mentioned political measure, Slovenia still has problems with the savers of the LB branch in Zagreb, Sarajevo, and Skopje. All these branches were independent banks until 1990.” (You can read the full article HERE)

Arms trade, war in BiH, and “non-paper”

But another question arises – namely, what interests did Kučan pursue after independence, when the project of a renewed socialist Yugoslavia based on the idea of the 1989 Basic Constitutional Charter at least partially failed. It is known that at that time, due to the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, there was an intensive arms trade, which is attributed to Janez Janša, who was the Minister of Defence until 1994. However, the Ministry of Defence actually caught a shipment of weapons at the airports that was not reported to the Ministry, and this was the reason why Janša was removed from the Ministry with the help of the Depala vas construct – also with the aim of removing him from politics forever, which failed. In all these years, thick books were published linking Janša with the criminal arms trade, under which journalist Blaž Zgaga is also signed.

However, in the middle of 2014, the same Blaž Zgaga, interestingly, even clashed with Milan Kučan himself (HERE). Maybe because he said too much about Kučan’s role? Needless to say, this also led to a (temporary?) break-up with Matej Šurc, with whom they co-created a notorious petition against censorship in 2007, for which Janša was allegedly responsible. At the same time, Šurc even publicly stated how Zgaga blackmailed Kučan’s publishing house Sanje for a fee for books, and allegedly even physically attacked the accountant. Was the nervousness at work, because the former party boss suddenly found himself on the pillory? In any case, the conversation with some stakeholders from the former SFRY in 2013 revealed many things (HERE), it turned out that those who revealed Kučan’s dubious role in the arms trade were right (HERE).

Croatian politician Slaven Letica was the one who revealed to the public that at the time of the disintegration of Yugoslavia there was a secret non-aggression agreement between Kučan and Slobodan Milošević, thus embarrassing all Kučan’s media “lawyers” with historian Božo Repet on the forehead in a television show. Esad Hećimović, the editor of Bosna, revealed an even more dramatic fact: The Kučan-Milošević agreement, according to him, also indirectly affected the bloody slaughter in BiH. And a logical conclusion: everyone with whom Kučan negotiated was convicted of war crimes. By the way, Slaven Letica died in October last year and now there is no danger for Kučan anymore that Letica would reveal another unpleasant fact from the time of the disintegration of the SFRY.

Who of the Slovenes is co-responsible for crimes in BiH?

And these facts also help us to understand why the “non-paper” affair has now taken place, which took the whole of Slovenia hostage in an attempt to discredit the government and rise to power, with BiH being only collateral damage. Also because it is a country that has been severely affected and quite unstable since the war. But the fact that the successors of the ZKS are fighting for power in such a dirty way did not happen for the first time, nor for the last time. Not with regard to BiH either – let us remember the abuse of Janša’s position from July last year regarding Srebrenica. On this occasion, Matej Šurc again pointed his finger at Janša, saying that due to his interventions in shipments of weapons, for which Izetbegović’s adviser Hasan Čengić had agreed with Kučan, the defenders of BiH could not defend themselves against well-armed Serbs who had all their weapons in their hands, which the Yugoslav People’s Army took with it in the autumn of 1991 upon its withdrawal from Slovenia. According to Šurc and like-minded people, Janša is said to be co-responsible for war crimes in BiH.

However, a completely different explanation is possible, which is related to another event, namely the disarmament of the Territorial Defence in Slovenia in May 1990. It has been known for some time that the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia, then led by Kučan, was aware of the disarmament campaign, and that at a time when the new Slovenian government was still being formed. However, when the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia issued an order to cease disarmament a few days later, the vast majority of weapons had already been removed.

Here, however, the question posed by Sebastjan Erlah in his 2016 column for Politikis.si arises: did not this act of disarming the Territorial Defence actually open Pandora’s box of all subsequent armed conflicts on the soil of the then disintegrating SFRY? (see HERE). Namely, the Croatian Territorial Defence was completely disarmed, except for the rebellious Serbs in the later Serbian Krajina. A few months after this action there was the first very dangerous outage in Knin (August 1990), which through months of uncertainty and individual incidents slowly grew into a completely open aggression of the communist YPA (which at first pretended to be neutral) and the landscape Serbs against Croatia, and a little later against Bosnia and Herzegovina.

And if we started with the role of Kučan as an envoy for BiH, let us end with that. According to media reports, the President of the Republic of Srpska, Milorad Dodik, was initially very upset about Kučan’s election. Who, however, said only a little later that Kučan is a man with a lot of political and human wisdom. So a statesman with knowledge, experience, and wisdom. An interesting turnaround. It is worth mentioning that the rather unfortunate search for a loan for the SDS in Republika Srpska ended in a scandal due to the fact that Republika Srpska is Kučan’s area of interest, and that informants have been monitoring all activities related to the financial project. And after all, congratulations always came immediately from Republika Srpska when one of Kučan’s candidates achieved great success in the Slovenian elections.

Enough for the wise? Let’s hope so.