By: Gašper Blažič

Slovenia has practically entered the “Years of Christ” with the 33rd anniversary of the plebiscite. Such anniversaries always bring reflections not only on the memory of the events at that time but also on the contemporary challenges facing the Slovenian state and the Slovenian nation.

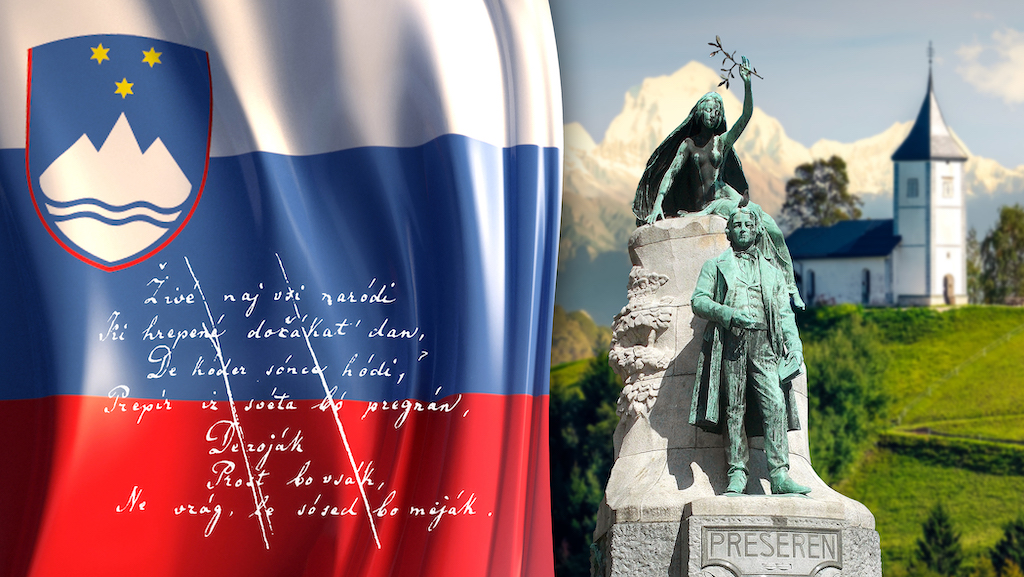

As stated by the then President of the Parliament, France Bučar, on the plebiscite day, December 23rd, 1990, during a special press conference in the evening at Cankar Hall, Slovenes, through the act of the plebiscite, became a nation in the true sense of the word, demanding their place under the sun. It is worth adding that the plebiscite was a central nation-building act, as it later helped us endure in critical moments – during the aggression of the Yugoslav People’s Army (YPA) and opposition from the West – ensuring that our independence was not merely a theatrical act to be shelved as an attempt at some adventure.

Censorship interventions by UDBA

It would be redundant to enumerate once again all the events that led to the plebiscite, but some certainly need mentioning, perhaps even those less highlighted. Recently, Igor Omerza published another book on the activities of the communist secret police, as part of the series Giants of Slovenian Independence, in which he specifically addressed the relationship between UDBA operatives and Igor Bavčar. They began actively monitoring him in the mid-eighties when he emerged as a critical thinker at events organised by ZSMS (Association of Socialist Youth of Slovenia). He was critical of party structures, especially the top figure of the Slovenian League of Communists (ZKS), France Popit. In the eighties, Popit was initially succeeded by Andrej Marinc and later by Milan Kučan. Bavčar criticised Popit for the political liquidation of Stane Kavčič in 1972. As Omerza recalled during the book presentation in mid-December this year, in the eighties, the actors, including the editorial board of the Journal for the Critique of Science (ČKZ) and the technical support at the publishing house (Mikroada), embarked on the publication of Kavčič’s diary after Niko Kavčič brought his notes following Stane Kavčič’s death (Janez Janša provides a more detailed description of this episode in the book Trenches from 1994). In Igor Omerza’s book JBTZ – Time Before and Days Later, the conspiratorial approach to the project of publishing Kavčič’s diary and memories is also described. They feared that the authorities would intervene prematurely and ban the project. In reality, it turned out that the regime’s secret police had their agents virtually present all the time, informing the top leadership of the Central Committee of the League of Communists of Slovenia (CK ZKS) about everything. At that time, Bavčar, who was still officially employed in the office of the deputy president of the Republic Conference of the League of Communists of Slovenia, Jože Knez (who was at that time preparing a conference on the green transition), greatly annoyed them. Bavčar wanted to change his employment and move to Mikroada. The minutes of a secret party session from Belgrade (where Kučan discussed with federal officials about possible repressive measures in the then SR Slovenia) actually reached the Mladina magazine through Bavčar. This was also the reason why the communist authorities immediately reacted, sending a high-ranking employee of the Ljubljana State Security Service (SDV), Miran Frumen, to the printing press. Frumen was tasked with preparing the ground for later arrests in the JBTZ case. This led to another censorship intervention in Mladina, where an article titled “Night of the Long Knives” (written under the pseudonym Majda Vrhovnik by Vlado Miheljak) was not allowed to be published. The article predicted repressive actions against dissenters.

Why they allowed the release of Kavčič’s diary

However, there was no such censorship intervention against the publication of Kavčič’s diary or the release of material for the new Slovenian constitution (both were published through ČKZ in the first half of 1988). In the book Trenches, Janša also explained why. Niko Kavčič – “Sultan”, a former UDBA (Yugoslav secret police) operative and a player in the “parallel economy”, who was forcibly retired after the fall of Stane Kavčič, still had channels connected to Ivan Maček – Matija. Kavčič’s diary could have been beneficial for Kučan since it might have helped him get rid of the inconvenient shadow of Stane Dolanc, the then Vice President of the Presidency of the SFRY, who, under normal procedures, could have become Tito’s successor in May 1989. Instead, he retired (similarly to Popit during this time), and the Slovenian party leadership, under Kučan’s guidance, opted for a referendum on whether to send their well-known figure (Marko Bulc, president of the Chamber of Commerce) or a less-known young banker (Janez Drnovšek) to Belgrade. In any case, the communist authorities did not intervene in the publication of Kavčič’s diary, but they were fully aware of it. They sought a way out of the dilemma of how to satisfy the angry federal and military officials, particularly incensed at Mladina for its “attacks” on federal defence secretary Branko Mamula. Ultimately, under Kučan’s leadership, the Slovenian party leadership had already adopted a new tactic that, instead of repression, emphasised a cultural struggle (as Mitja Ribičič put it, “with a book against a book”). They even rejected attempts by the chief federal prosecutor in Belgrade, Miloš Bakić, to prosecute Slovenian dissidents. Instead, they chose to engage in sharp public propaganda against issue 57 of Nova revija and later against the actors involved in the draft for the new Slovenian constitution.

How Vasiljević slipped

Nevertheless, a decision was reached that, to avoid the “excessive boldness” of dissenters, some of the most outspoken and dangerous ones should be caught and handed over to Belgrade’s executioners, thus washing their hands of the matter. It was this decision that led to the later JBTZ affair. However, the SDV actors had to replace the “corpus delicti” – instead of the stenogram of the party session that led UDBA members to target Mladina, they chose a mutilated copy of a military document. This document was brought to the editorial office of Mladina by YPA employee Ivan Borštner, handed over to the regional editor David Tasič, and later taken by editor Franci Zavrl to Janša, under the influence of anger due to retaliatory attacks by the “Narodna armija” magazine on Mladina. At that time, a source from the SDV reported to their superiors that Janša had received some “military orders” from Zavrl. The SDV was evidently convinced that by exemplarily arresting a few dissenters and handing them over to the military, they would trigger enough panic to calm things down. However, they miscalculated and, in the process, triggered an unexpected reaction: the Committee for the Protection of Human Rights was formed, led by the aforementioned Igor Bavčar. Large gatherings were organised in Ljubljana, causing panic among military officials. It was during this time that Colonel Aleksandar Vasiljević, Janša’s interrogator in prison and one of the officials of the YPA Counterintelligence Service, lost his temper. He forcefully presented the truth to Janša, stating that Slovenes constituted only eight percent of Yugoslavia’s population and even if they were all killed, Yugoslavia would not lose much. This incident shattered the last illusions that Yugoslavia could be a viable option for the Slovenes in the future. Consequently, new political parties, constitutional movements, and the presentation of the May Declaration followed, demanding the “sovereign state of the Slovenian nation”. Unlike the later regime-approved “enlightened” Basic Platform, the May Declaration did not mention the renewal of Yugoslavia and the renewed socialism.

The thorny path to the plebiscite

However, the path to the plebiscite was not straightforward, as it first required the victory of DEMOS and the election of the DEMOS government. Otherwise, it is questionable whether the main events leading to independence would have occurred at all. In the spring of 1990, among the parties, the League of Communists of Slovenia – Social Democratic Party (ZKS-SDP) still garnered the most votes. This means that it was worth undertaking a risky manoeuvre three months earlier, in January 1990, at the last congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. At that congress, they proposed quite daring reforms, were outvoted, and then left the congress prematurely. This decision was, of course, influenced by fear, as the images we witnessed on TV during the confrontation with the Romanian communist tyrant Ceaușescu were still fresh. This fear was also evident when the republican secretary for internal affairs, Tomaž Ertl, who just a few months earlier compared dissenters to the “White Guard” at a meeting in Belgrade, refused to appear at the handover to the new secretary or minister, Igor Bavčar, in May 1990. They found Bavčar with empty drawers, and the ongoing disarmament of the Territorial Defence (TO) was taking place with the silent consent of Milan Kučan, who was already the president of the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia and apparently well-informed about the events. However, as the supreme commander of the Slovenian armed forces, Kučan seemed indifferent, as he did not appear at the TO assembly in Kočevska Reka just before the plebiscite. Instead, the speech was delivered by Prime Minister Lojze Peterle, who thrilled the public with his legendary remark that the scent of the Slovenian army was in the air.

The EU does not threaten us, but can help us

And what are the challenges facing Slovenia and the Slovenes today? Some of this was explained by Dr Vojko Obrulj, who in 1991, as a member of MORiS, a special unit of the Slovenian Armed Forces, assisted in the expulsion of the YPA from Slovenia. He then spent six years in Kočevska Reka contributing to the establishment of the professional concept of the Slovenian Armed Forces. As he stated at the celebration of the anniversary of the Territorial Defence assembly in Kočevska Reka, they fought on their own territory at that time, without military allies, but did not lose an inch of Slovenian soil. After more than thirty years, the challenges are, of course, somewhat different, as we now have our own country, culture, language, and territory (which, of course, we can squander due to our own foolishness). Now the question arises whether the European Union is still in the national interest. However, as Dr Obrulj says, for the European Union, “the interconnectedness of European countries for lasting peace and the promotion of the national identity of each nation is extremely important, as it enriches it. Therefore, we must pay more attention to preserving national identity.” As he points out, the world, the EU, and Slovenia are facing new challenges that are complex and interdependent. “We must realise that challenges and problem management are not outside us but often depend on ourselves. /…/ The Slovenian nation has formed over centuries under the influence of Christian values (as Primož Trubar said – dear Slovenes, you must read and write in Slovenian), and we must not neglect this. With great sacrifice and a desire for freedom and peace, we fought for our country in 1991. Let us respect human rights, while not forgetting our civic rights and duties. Our homeland is here, our land, our country, and our way of life,” said the keynote speaker.

And for further consideration: can the nation and the state be part of a cult or even a religion? For the average public, both are values, but a value is not the same as a cult. Although with the plebiscite, Slovenes fought for and elected a national state, it does not necessarily mean that we have chosen national self-sufficiency and isolation. Therefore, we can say that the European Union cannot threaten us as long as we build on the right values. As Dr Obrulj stated: “The task of this generation is and must be the preservation of the Slovenian nation. If we have achieved independence, we are obligated to persist and enable the next generation to endure and grow based on our values.”