By: Bogdan Sajovic

In 1989, communist regimes were collapsing across Europe like houses of cards. The “reformists” rushed to depose the party dinosaurs. The Berlin Wall had fallen due to bureaucratic ambiguity. With the exception of Romania, changes took place without bloodshed.

Slovenian independence became a real possibility in the mid- -1980s, when communist regimes in Europe began to falter. Communist Yugoslavia was somewhat different from other European communist states. While communism was imposed on these countries in 1945 with the help of Soviet tanks, Yugoslav communism was of a much more autochthonous origin, as throughout the Second World War, under the guise of “fighting the occupier”, the Yugoslav communists were killing their actual and potential political opponents and established their power in the “liberated territories”. The massacre at the end of the Second World War, when hundreds of thousands of opponents of communism ended up in 600 killing fields scattered across Slovenia, was only the final seal of the communist takeover. The brutal massacre and, consequently, the extermination of the anti-communist elite, allowed the Yugoslav communists to be more ‘in the saddle1 than their communist comrades in other European countries, who mostly held power with the help of Soviet tanks. With reference to this, they bloodily suppressed several attempts to overthrow the communists in East Germany in 1953, in Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia in 1968. In 1980, the Polish party imposed a military dictatorship in the hope of appeasing its red comrades and preventing fraternal tank intervention.

The crisis of the communist system

However, in the mid-1980s, Soviet communism had entered a complete crisis. Due to incompetence, dogmatism, and corruption, the Soviet Union was on the verge of economic collapse. The party attempted to “modernise the system” through the “reformer” Mikhail Gorbachev, which turned out to be an impossible task. The reform plan, that is the so-called perestroika, failed and it quickly became clear that the system could no longer be rescued, but it was also becoming increasingly clear that the Soviet Union was losing the desire to keep communism in “fraternal states” with tanks. This further encouraged opponents of communism across Eastern Europe and led to the events in 1989, when communist regimes across Eastern Europe collapsed like houses of cards.

The Poles washed away the red regime

It all began in Poland, which had the strongest and most diversified opposition movement in Eastern Europe in Solidarity. The violence of the party and its repressive organs did not suppress the movement, it even inflamed it. When secret police assassinated Jerzy Popietuszko’s father, a prominent anti-communist preacher, in 1984, the revolt was so strong that the Communist Party itself renounced its assassins and sent them to prison. The pressure on the Polish party intensified and in February 1989 it bowed down and agreed to negotiate with Solidarity. To begin with, it lifted the state of emergency, recognised Solidarity and promised free elections in June 1989. On June 4, in the first free elections after World War II, Polish voters literally washed away communism with their votes.

The “reformists” were removing the party dinosaurs

After Poland, Hungary followed and in the spring of 1989, the “party reformists” forced the old Stalinist autocrat Janos Kadar to resign, proclaimed the opening of borders and freedom of association. The Hungarians, who had not forgotten the bloody suppression of the 1956 uprising, were not satisfied with these cosmetic corrections, and pressure on the party continued until the party finally relented and adopted a new constitution in October that abolished the one-party system, allowed free elections and sent communism to the dump of history.

Following an example of Poland and Hungary, the Czechoslovak anti-communists also began to put pressure on the ruling Communist Party, mainly through mass rallies. The party tried to suppress the rallies by carrying out mass arrests, but they quickly realised that the protesters were too many. In October 1989, the Czechoslovak Party accepted the inevitable and proclaimed freedom of assembly, the opening of borders, and promised free multi-party elections for December and an amendment to the constitution.

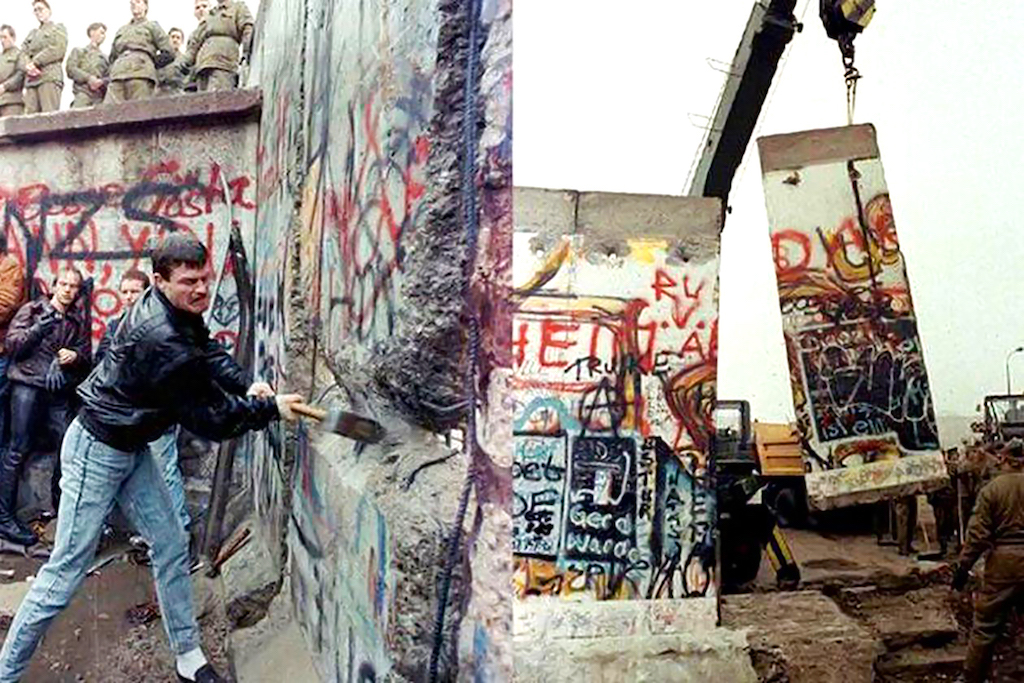

East Germany was a somewhat special case. The Berlin Wall was, so to speak, a symbol of “eternity” and the power of the communist regime, and the old Stalinist Erich Honecker tried to preserve it. Crowds of East Germans began traveling to Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, where they turned to West German embassies for asylum, or rather, they took advantage of the recent opening of borders and moved to the West. An enraged Honecker sought to isolate the country by closing all borders, which would finally sink the already crumbling East German economy and, in addition, lead to difficulties in supplying the Soviet army, which was still stationed in East Germany at the time. The party “reformists”, therefore, quickly removed Honecker and announced the reopening of the borders. While they were considering reopening the borders with only Poland and Czechoslovakia, due to unclear wording, the party functionary announced the opening of all borders at an evening press conference on 9 November 1989. Immediately after the conference, thousands of Berliners marched towards the border crossings at the Berlin Wall. Confused police officers did not dare to use force, so they opened the crossings. This is how the Berlin Wall fell, and with it the East German communist regime.

But it was not just the East German regime; the “reformist” faction in the Bulgarian party thought that it was best to extinguish a possible uprising and secure some bonus points, so in early December it quickly retired the old autocrat Todor Zhivkov and promised to amend the constitution and introduce multi-party democracy.

The Carpathian vampire persisted to the end

After the overthrow of the communist regimes in most countries behind the Iron Curtain without bloodshed, the Romanian autocrat Nicolae Ceauçescu decided to persevere to the bitter end. His secret police opened fire on 17 December, killing dozens of protesters in Timisoara. In the following days, the protests intensified despite the deaths (or due to them), and on 21 December, hundreds were killed when the autocrat ordered to open fire on the crowd again. But the very next day, the onslaught of the crowd broke through the defences of the government palace in Bucharest and overthrew the communist regime. Ceau§escu and his wife (partner in crime) Elena escaped from the enraged crowd by helicopter leaving the capital. A few days later, they were caught and shot after a hasty trial in Targovishte on 25 December.

The bloody end of Ceau§escu’s rule, the “Carpathian Vampire”, occurred in 1989, a year in which all European communist regimes imposed on European nations by Soviet tanks collapsed. However, the Yugoslav (and thus Slovenian) communist regime lasted a little longer, but it was the shots in Targovishte that “convinced” the Slovenian communists that they had agreed to multi-party elections and to step down from power. Nevertheless, this “descent” enabled the Communists to retain much of their political power, though it also enabled Slovenia’s independence and the break-up of Yugoslavia, which is something that many Slovenian communists still mourn. After all, to paraphrase their Secretary General Milan Kucan, an independent Slovenia had never been a preferred option for them.