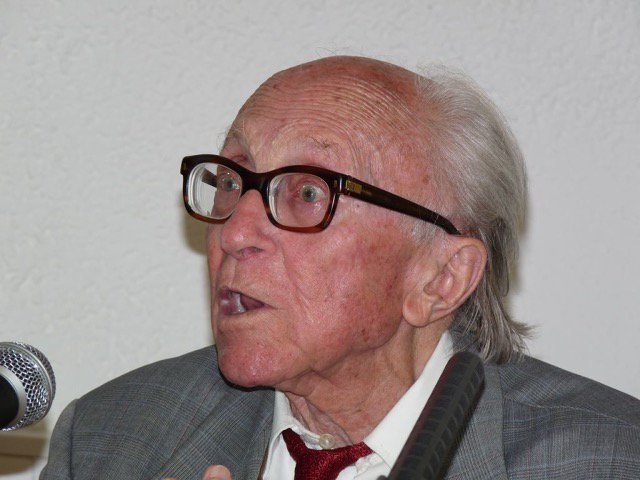

Boris Pahor, an acclaimed Slovenian writer from Italy’s Trieste, a Nazi camp survivor and an outspoken fighter against all totalitarianisms, turned 107 today. While only last year he still attended a special event celebrating his birthday, an online event will be organised this year due to his health concerns.

In a video posted by the Ljubljana-based publisher Mladinska Knjiga, Pahor points to the three main postulates for the 21st century – freedom, justice and truth.

“Freedom – because God created man and wanted him free. Also the Holy Scripture, at the beginning of the Old Testament, says that he wanted him free. He could have made him not free.

“Justice – because man has to adhere to what is true, right and necessary. It is right that every man have enough food and income, for himself and for the children.”

The third postulate is truth in the sense that everyone must know what is going on, said Pahor, stressing that the truth must not be kept secret.

Asked about the stamina he has at 107, Pahor said he had inherited it from his father, a very able-bodied man, while his mum had also been quite active.

“Then there is also the conviction that being a camp survivor, I have to be a witness to truth. My stubbornness that I have to speak about Nazism as best and as objectively as possible was born in the book Necropolis.”

When this autobiographical novel was first published in Slovenian in 1967, it was largely overlooked, but in 1990 it was translated into French to critical acclaim.

The novel has since been translated into many languages, and was also declared the book of the year in Italy in 2008.

Necropolis starts with Pahor’s visit to the memorial at the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp, also bringing an account of his imprisonment at the other concentrations camps – Dachau, Dora, Harzungen and Bergen-Belsen.

Pahor, who was also a strong opponent of the communist regime in Yugoslavia, has dedicated his life to highlighting the dangers of totalitarian regimes.

A fighter for the rights of endangered languages and cultures, himself being a member of the Slovenian minority in Italy, he often speaks about the need to know history and to honour one’s identity.

The writer believes that being aware of their national identity is key for Slovenians to survive as an ethnic community in Italy and for humanity in the world.

As a child just before he turned seven, Pahor saw the Slovenian National Hall in Trieste being burnt down by Fascists in 1920.

When the centre was finally symbolically returned to the Slovenian minority on 13 July this year, he received Italy and Slovenia’s highest national honours.

Slovenia decorated him for his extraordinary merit in enhancing understanding and integration among nations in Europe and in his relentless promotion of Slovenian identity and democracy. Italy decorated him with the Knight of the Great Cross order of merit.

Despite his initial reluctance to accept the orders of merit, he decided to accept them and dedicate them to all those who had died in concentration camps.