By: V4 Agency

“It was a mistake to criticise Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban for raising a rasor wire fence at the border in 2015,’ said Danish Minister of Immigration and Integration Mattias Tesfaye. Hungary was the first to build a physical frontier fence to protect its own and the EU’s borders from illegal immigrants. At that time, Hungary was widely criticised, but later countless countries followed suit. The following compilation of V4NA shows that the number of fences has increased six-fold over the last six years, with physical border closures being erected at at least fifteen border crossing points in various country across Europe, who have recognised that this is the most effective way to protect borders. Despite an obvious tipping of the scales, the European Commission is still unwilling to support the construction of fences by member states.

“We are not financing the construction of fences or barriers at the external borders,” responded Alexander Winterstein, spokesman for the European Commission back in 2017, when asked if the EU would be willing to reimburse half of Hungary’s border protection costs.” On 31 August 2017, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban wrote to the European Commission in order to recoup half of the 270 billion Hungarian forints (800 million euros) spent on border protection measures. The Commission‘s position was that the government could receive money for certain elements of the border control system, but not for the construction of the fence.

Interestingly, on 16 January 2017, the English-language page of Euractiv, a political portal of Brussels, published an article entitled “Lithuania to build Kaliningrad border fence with EU money”. On 5 February 2017, the British Daily Express reported that Latvia had completed its anti-migrant fence along its Russia border and received £ 1.6 million (1.8 million euros) in funding from the European Union for the first stretch of the frontier, which was roughly 20 kilometres long. The contradiction between Mr Winterstein’s statement and the information in the articles was pointed out by a Hungarian portal, whose editorial office was subsequently contacted by the Representation of the European Commission in Hungary. The portal was informed that the “rumors described in the article are wrong and that the European Union supports the protection of external borders by assisting its member states in setting up surveillance and border control systems, among other things. However, it does not in any case finance the establishment of border fences and has not previously accepted such requests, including in the case of the countries referred to in this article.“ That is, they upheld their previous position that they do not provide sources for erecting fences.

With or without resources from Brussels, the fact remains that with growing migration, the number of anti-migration protective measures, such as the number of border fences, have exponentially increased since 2015. According to data collected by DW, between 2000 and 2021, the number of completed, started, or announced border fences cropping up around the world have more than quintupled, from 16 to more than 90. As a result of increasing migratory pressures starting in 2015, and due to the EU’s failed immigration policy, a number of border fences have also been built within the European Union.

Even before 2015, fences were built on EU borders

Prior to the outbreak of the 2015 migrant crisis, only three member states having external borders applied to erect fences to prevent migrants from entering EU territory: Spain, Greece and Bulgaria.+

Spain was the first to erect a fence, completed in 2005, and expanded in 2009. The Spanish government’s ongoing problems with African migrants prompted the building of border fences in the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla in the Spanish Exclaves region of Morocco, protecting the Moroccan-Spanish border for 8.7 and 12 kilometres, respectively.

Spain was followed by Greece, which built a fence along her short border with Turkey in 2012. The fence changed the route of migrants coming to Europe and diverted the wave of immigration to Bulgaria, or to the Greek islands of the Aegean Sea. This June, Greece embarked on expanding the fence, fearing that the situation in Afghanistan would trigger a new influx of migrants descending on Europe, as it happened in 2015. The extended border barriers were completed by 21 August. The new border protection in the Evros region of Eastern Thrace is an extension of the existing 12.5-kilometre-long fence. A 5-meter tall steel fence was erected on the section and a surveillance system was also installed.

“We can’t wait passively for potential arrivals. Our borders will remain inviolable,” said Greek Defense Minister Michael Crisocoidis on 20 August.

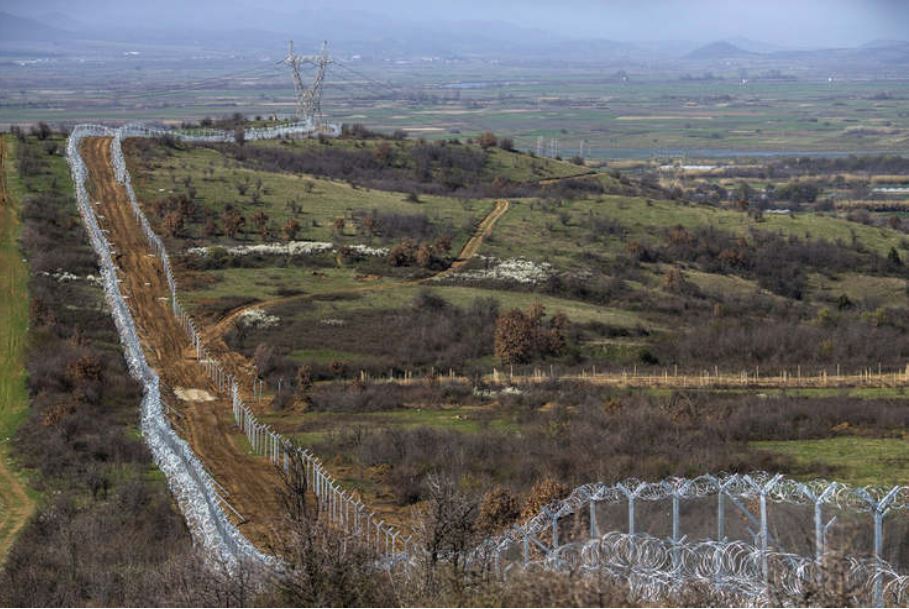

As a result of the fence established in 2012, migrant masses from Greece headed for Bulgaria instead. The Bulgarians responded in 2014 by building their own 33-kilometre fence on a stretch of the Turkish border.

Of course, the EU was already voicing objections, with Nils Muizniesk – the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, for example – warning the country that it was “not a good idea” to close the border with a fence. At the same time, Bulgaria’s new fence and tighter border controls reduced the number of illegal newcomers entering the country by half.

In 2015, migrants from Greece were already making an effort to reach mainland Europe via Macedonia.

The 2015 migrant crisis highlighted the importance of border protection

In 2015, Macedonia erected a fence on certain sections of the Macedonia-Greece border where migrants made regular attempts to enter the country. The goal was to divert immigrants to legal crossing points.

The Macedonian government also announced in late 2015 that it would only allow Syrian, Iraqi and Afghan nationals fleeing war into its territory; other economic migrants would not be allowed entry. With this step – in addition to the physical barrier – legal instruments were also introduced to protect the border. By early 2016, however, thousands of people had accumulated at the border, and the crowd also managed to break through the fence.

In order to fortify border protection, the construction of a double fence was finally started – also in early 2016 – along the Greek-Macedonian border for a stretch of about 27 kilometres. Construction began three metres from the existing fence, and the intermediate area was designed so that border guards could patrol there.

In the worst year of the migrant crisis, Hungary closed some sections of its green border with Serbia in 2015, a decision made on 17 June 2015 by the Hungarian government. The Hungarian Armed Forces installed a 4-metre-high border barrier along the 175-km section of the Hungary-Serbia frontier. This was extended further to the Croatian border by Hungary in October 2015, as the Croatian government transported all immigrants entering Croatia to the green border between the two countries. In 2015, the Hungarian government was also planning to extend the southern border barrier toward Romania.

In 2016, the Hungarian government decided to establish an additional row of fences on the Hungary-Serbia border to bolster the country’s defence. This new line of defence was equipped with the most modern technical equipment.

According to Hungary’s government, the first border barrier alone cost around at 12 billion Hungarian forints (35 million euros). In September 2017, PM Viktor Orban wrote a letter to Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission, asking the EU to contribute by reimbursing 50 per cent of Hungary’s border protection costs. The protection of Europe’s borders cost the country a total of 270 billion forints (800 million euros), Mr Orban stated at the time.

For a time, Austria opposed the construction of the fence. Some Austrian politicians even likened Hungary’s measures to the darkest periods of the 20th century, but after a while Austria also began to realise that open borders were not an option. In the autumn of 2015, it was announced that a fence would be built on a 4 kilometre-section of the Slovenian border, even though former Austrian Chancellor, Werner Faymann said that “a distinction must be made between building a border fence and building a “gate with side parts“.

By September 2016, Austria reached a point where it was planning to build a fence on three sections of the Austro-Hungarian border: at Nickelsdorf (Hegyeshalom), Heiligenkreu (Rabafuzes) and Moschendorf (Pinkamindszent), the ORF Burgenland portal wrote. In the end, only the foundations of these fences were laid along a stretch in Hungary used by hundreds of thousands of migrants to cross into Austria during the 2015 wave. The goal was to enable authorities to erect a fence swiftly on these foundations, if needed.

Following the big migration crisis of 2015, Norway erected a 200-metre long and 3.5-metre tall wire fence along the Russian border, arguing that the country should take its responsibility for the Schengen agreement seriously. Justice Minister Anders Anundsen justified the need to build a fence by stressing the importance of keeping track of indivisuals entering either Norway, or the Schengen area. He pointed out that more than 5,500 asylum seekers, both refugees and migrants, entered Norway at the Storskog checkpoint along the Norway-Russia border. The immigrants took the so-called Arctic Migrant Route across Russia’s Kola Peninsula.

There have been only a total of two incidents since the border barrier was built. In July 2017, Russian border guards arrested two individuals for trying to pass the border going round the checkpoint. In August 2017, a Syrian citizen ran through the Russian border control and tried to scale the fence, but he was stopped by the Russian border guards.

Although no fence was erected between the two Scandinavian countries, Sweden and Denmark, in January 2016, strict border controls, including ID verification, were introduced on the Oresund Bridge connecting Sweden and Denmark to stem a major influx of migrants. Since 1950, there was no photo ID check for people wishing to cross the Denmark-Sweden border by train, bus or boat. Travelers failing to present a valid photo ID were turned back at the border.

“My Europe takes in people fleeing from war, my Europe does not build walls,” said Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lofven on 6 September 2015. But three months and about 80,000 asylum seekers later, he was forced to admit that the system could not cope with the influx of migrants. Almost 163,000 people applied for asylum in Sweden in 2015, the highest in Europe in proportion to the country’s population.

In response to the 2015 migrant crisis, Slovenia also constructed a razor-wire fence on a 179-kilometre section on the nearly 670-kilometre long border with Croatia in an effort to block the passage of migrants from the Middle East and Africa towards Western Europe.

In September 2016, France and the UK launched the construction of the so-called Calais Border Barrier to prevent irregular migrants from entering the UK unlawfully via the Channel Tunnel and from the port of Calais. Work was completed in December.

The Calais Border Barrier is a 4-metre high, 1-kilometre long concrete wall that runs along the main road beside the so-called “Jungle” camp set up by migrants. Calais Mayor Natacha Bouchart attempted to block the construction of the wall, arguing that it will be unnecessary once the the so-called Calais Jungle will have been demolished. However, her argument was rejected by the court, and the wall was built.

Earlier, in the summer of 2015, France built a 39-kilometre barrier to block access to the Channel Tunnel and erected a 39-kilometre long section to protect the port and the bypass. These two fences were constructed on the initiative of the French government, but their costs were fully funded by the UK.

Serbia decided in 2020 to build a fence along a section of the Serbia-Macedonia border, the Balkan office of Radio Free Europe reported at the time.

Presevo Mayor Sciprim Arifi told Radio Free Europe that the construction of the fence was part of the agreement with the European Union to protect Serbia from mass migration. He added that the fence contributed to the EU’s integration processes, noting that he himself did not support such attitude towards refugees.

However, European Commission spokeswoman Ana Pisonero stressed that although the EU was providing significant financial and technical support to the Western Balkan countries to tackle migration issues, building a fence was not part of any agreement.

She said that the EU provides significant funding to help Serbia manage migration, adding that the country received 100 million euros for this purpose in 2015, for instance. “Still, those funds do not include building fences that, as it was wrongly reported, were not part of any agreement with the EU,” the spokeswoman said.

Fences along the Russia and Belarus borders

On 23 August, Polish Defence Minister Mariusz Blaszczak announced that Poland will build a 2.5-metre high fence along its border with Belarus.

Recently, authorities have seen a significant rise of migratory pressures on the Poland-Belarus border, with sharp spikes of migrant numbers arriving from the Middle East through Belarus to cross the eastern border of the European Union. The rising number of arrivals on the border is an “organised activity”, Poland says, arguing that Belarus is using migrants as part of a “hybrid warfare”. Since early August, more than two thousand migrants tried to cross over from Belarus to Poland illegally.

Construction began at the end of August. A nearly 100-kilomtre long section of the border has already been protected with a barbed-wire fence, and now authorities are planning to build another 50-kilomtre long fence. In addition, the defence minister increased troop numbers deployed to support border guards to 2 thousand. Until now, it was the responsibility of 900 soldiers to assist the guards along the most dangerous 187-km section of the 418-kilometre-long Belarus border.

The Lithuanian parliament has also voted to build a fence on the Belarus border to prevent the entry of Iraqis, Afghans and other non-EU migrants. The border barrier is planned to be completed in the autumn of 2022. Lithuania aims to build a 4-metre high metal fence with a razor wire to protect its frontier with Belarus at an expected cost of 152 million euros.

In connection with the fence, a spokesman for the EU said that the bloc “does not finance fences or barriers”. So far, the EU has offered help in the form of border guards and supplies instead

In order to boost its border defence, Lithuania decided as early as in 2017 to build a wire fence along its border with the Russian region of Kaliningrad, tucked between Latvia and Poland. The agreement to erect the fence was also signed that year between the Lithuanian Border Guard and the general contractor. The plan was to build a 44,6-km fence along the Lithuania-Russia border section, which is the joint external frontier of NATO and the European Union.

Latvia announced in 2015 that it intends to build a 135-km fence along its joint 173-km border section with Belarus. To cost of implementation was estimated to reach 27,6 million euros and the plan was to complete the project by 2021, but the construction was put on hold due to shortcomings and irregularities highlighted during the state audit. In early August, Latvia’s government declared a state of emergency – in effect until 10 November – along its Belarus border, authorising border guards to use physical force and special tools to apprehend and return illegal border violators.

Criticising Hungary’s PM because of the fence was a mistake

“It was a mistake to criticise Hungarian PM Viktor Orban for having raised a barbed-wire fence along the border in 2015”, said Mattias Tesfaye, Denmark’s minister for immigration and integration, in connection with interior ministers’ meeting in Brussels, which also focused on the situation in Afghanistan. The EU’s interior ministers agreed that the bloc must prevent a repeat of the migrant crisis of 2015.

Mattias Tesfaye underlined that the events of 2015 “cannot be repeated”. Back then, we saw migrants marching through Europe’s highways and we were unable to protect our external borders. Charitable organisations were also short of money. Now, everyone must reach deep into their pockets, Mr Tesfaye said, adding that the international community cannot be frugal when it comes to providing humanitarian aid.

He stressed, that Demark believes in strong borders.

“And not just between Europe and the neighbouring countries, but also at Turkey’s eastern, and Tunisia’s southern borders. Denmark plans to provide assistance to these two countries to strengthen their borders”, the minister said.

The situation unfolding in Afghanistan appears to have highlighted the importance of border protection once again. In the six years since the migrant crisis of 2015, most EU member states have come to recognise that it is impossible to tackle migration without strong border protection.