By: Matej Markič

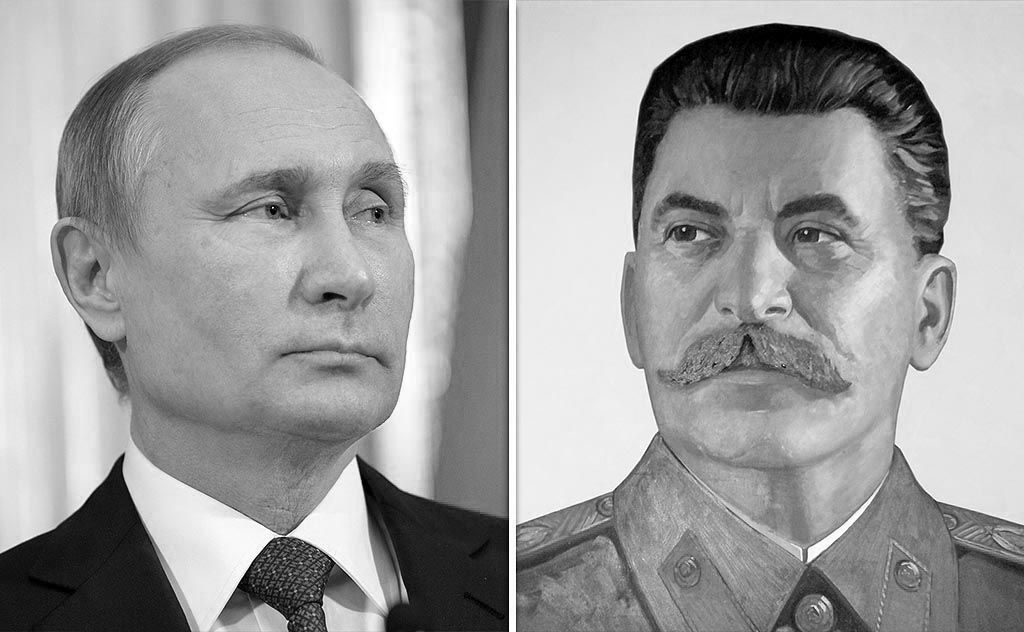

In this article I will discuss and present the similarities between the aggressive, militaristic, and imperialist tendencies of the Soviet Union during its existence between 1917 and 1991 and today’s military appearance of the Russian Federation on the international stage, also throughout its existence, from 1991 to today. In the article, I will first present how both countries have always violently acted against politically undesirable minorities and any groups that have tried to secede from their home country or at least achieve a greater degree of autonomy, then describe how the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation carried out military aggression against neighbouring countries, and I will conclude the article by comparing the similarities of imperialist tendencies and establishing a military presence in the countries of the so-called “Third world”.

Violence against minorities and gross repression of all autonomist and separatist movements

The Russian Civil War itself (1917-1922) clearly showed that not all the inhabitants of the emerging Soviet Union (hereafter the Soviet Union) agreed with the Marxist-Leninist ideas spread by the Bolsheviks under Lenin. Not only did the October Revolution of 1917 and the consequent takeover of power by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union hurt many class and politically different groups (monarchists, Russian nationalists, social democrats, etc.), but dissatisfaction with Russian communists was also evident among members of many national minorities who had already sought liberation or at least a greater degree of autonomy during the Russian Empire. The Bolsheviks showed no mercy for the freedom-seeking members of the Central Asian nations, the Ukrainians and the Karelians, and suppressed the attempts at their independence in blood. In the same way, they wanted to settle accounts with the Finns and the Baltic nations between 1918 and 1920, but in this case they failed.

Moreover, during World War II and immediately after its end in 1945, the Red Army and the Soviet Secret Service, the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (hereinafter NKVD) and later the MGB/KGB, suppressed all the nationalist and anti-communist initiatives of the subjugated nations that wanted to shake off the Soviet shackles. Thus, the NKVD, then led by the infamous Lavrentiy Beria, began mass arrests, and forced expulsions of “unreliable” ethnic groups with a long tradition of resistance to Moscow in 1944, at Stalin’s direct behest. These were primarily Chechens, Ingush, Crimean Tatars, and other ethnic groups who lived mainly in the south-western USSR, i.e., those areas that had been under German occupation for several years. After the withdrawal of the German Wehrmacht from the USSR in 1944, Stalin accused members of the ethnic groups living there of collaborating with the Nazis, resulting in hundreds of thousands of Azeris, Chechens, Circassians, Ingush, Kurds, Tatars, Ukrainians, and others imprisoned in gulags or exiles to Siberia in the following years. Tens of thousands died in Soviet gulags and remote parts of the Soviet Union, where they were deported, and they did not return home until after Stalin’s death in 1953.

In this case, the Russian Federation is quite similar to its predecessor, as the current Russian government also has virtually zero tolerance for any autonomist tendencies that may arise among the non-Russian, mostly Muslim, population of the Russian Federation. Thus, Russian forces intervened twice (in 1994 and 1999) in Chechnya, where strong separatist movements emerged in the 1990s, but were largely suppressed by Russian military units by the end of 2000, although individual operations continued until 2009.

Aggression against neighbouring countries

Ever since the formation of the Soviet Union in 1917, the Bolsheviks have sought to export the communist revolution beyond Soviet borders and have chosen no means to achieve their goals. As early as 1920, at a time when the Russian Civil War was not even over, the Red Army had already crossed the western borders of the Soviet state, with the aim of seizing as much territory as the state had lost when Lenin concluded the Brest-Lithuania Peace Treaty with the Central Powers in March 1918, by which the Soviet Union renounced large-scale territories in what is now the Baltics, Belarus, Finland, Poland, and Ukraine in exchange for peace. Moreover, the Soviet leadership hoped that their troops would succeed in penetrating the west, to bring communist ideology to European countries. Soviet troops led by Leo Trotsky, Mikhail Tukhachevsky, and Joseph Stalin became embroiled in fierce battles with Polish and Ukrainian troops, and at the beginning (1919 and early 1920) also achieved some victories and began to penetrate Central Europe, however, they were severely defeated in the Battle of Warsaw in August 1920, when they were defeated in the area of the then Second Polish Republic by the Polish army under Marshal Józef Piłsudski.

Soviet appetites for foreign territories continued in the following decades, leading to the signing of a treaty of friendship and non-aggression with fascist Italy in 1933 and with Nazi Germany in 1939 (i.e., the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact), in which the two dictatorships also agreed on military occupation and the mutual division of territories in northern, central, and eastern Europe. Thus, despite its declaratively anti-fascist character, the Soviet Union found itself in alliance with the Axis powers, whose basic ideology was fascism or Nazism. In September 1939, the Soviet army, together with Hitler’s troops, invaded Poland and divided it together with the Germans, and later occupied the Baltic states, Bessarabia, and northern Bukovina in Romania, and much of Finnish territory.

Imperialist ambitions after World War II

Even after the end of World War II, when the Red Army in a counter-offensive led by General Grigory Zhukov penetrated all the way to Berlin and much of Europe was in ruins, Stalin did not give up on imperialist ambitions. Thus, Soviet forces in the eastern part of Europe, previously liberated by Nazi occupation, first occupied the Baltic states, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia in 1944, and then with coups, in Bulgaria in 1944, Hungary in 1947, and Czechoslovakia in 1948, or rigged elections, in Romania in 1946 and in Poland in 1947. They thus established a wide network of subordinate communist regimes, which in 1955 also united them into a single military alliance called the Warsaw Pact. The Soviet Union also had its own military units always present in the area, which also intervened by force, if necessary, to suppress any attempts at reform and democratic change in these countries. Such an intervention took place first in the German Democratic Republic in 1953, then in Hungary in 1956, and in Czechoslovakia in 1968. However, things did not always go as expected by the Soviet authorities, and so many Eastern European de jure communist states, managed to shake off Soviet domination. This was already possible in Yugoslavia in 1948, which after the so-called conflict with the Informbiro virtually severed ties with the Soviet Union, and in 1961 and 1968 the Yugoslav example was followed by Albania under Enver Hoxha and Romania under Nicolae Ceauşescu.

The most famous example of the Soviet occupation of another country during the Cold War is certainly the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which took place in late December 1979. Afghanistan, which bordered on the Soviet Union, had a socialist rule in the years before the invasion, a government that took power through a coup, and the Afghan Communist Party was relatively small and, with its secular and socially progressive ideology did not enjoy excessive sympathy among Afghanistan’s deeply religious population. As the weak Afghan government led by Hafizullah Amin was unable to cope with the mass resistance of the mujahideen, which spread virtually across the country, the Soviet Union decided to take matters into its own hands, which eventually led to 10 years of occupation of Afghanistan by the USSR, which also could not cope with the guerrilla rebels and was forced to withdraw in 1989.

Like the Soviet, the Russian authority is also not unfamiliar with violent incursions into neighbouring countries. The Russian government even considers them necessary to maintain Russian domination. A few months after the collapse of the Soviet Union (December 1991), the newly formed Russian Federation chose the first target to expand its geopolitical ambitions, the former Soviet Republic of Moldova, which became an independent state in 1989. Despite the declaration of independence and the establishment of its own armed forces, many members of the Soviet army remained in eastern Moldova, who did not merge with the newly formed Moldavian army but in March 1992, with strong Russian support, began a conflict with it and in the six-month war seized extensive territory in eastern Moldova. This territory, today known as Pridnestrovie or Transnistria, was therefore declared a new sovereign state, which is still internationally unrecognised.

The next target of the Russian military machine was Russia’s southern neighbour Georgia, which has become increasingly pro-Western since 2004, when Mikheil Saakashvili took power in the country and chaired the country in the South Caucasus between 2004 and 2013. As Saakashvili’s ambitions to join the European Union and the NATO pact seemed unacceptable to Russia’s leadership, Russian troops invaded Georgia in August 2008 and forcibly took Abkhazia and South Ossetia regions from it in the ten-day war that followed. The regions have since become de facto independent states, although they are de jure recognised as such by only a handful of states.

In 2014, Russia’s march of conquest moved to the borders of the European Union. Large demonstrations against the pro-Russian Ukrainian government called “Euromaidan” erupted in Ukraine that year. Russia took advantage of the general chaos in the country and the political vacuum created by the escape of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych and invaded Ukraine, immediately annexing the strategically important Crimean Peninsula and then focusing on destabilising and de facto occupying large areas of Ukrainian east, centred in the provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Imperialist foreign policy and military interventions in the countries of the so-called “Third world”

Just as Soviet troops crossed the borders of European countries during and after World War II, they were involved in many other interventions and military missions around the world, especially during the Cold War, in the second half of the 20th century. In Africa, during the Angolan Civil War (1975-1991), the Soviets strongly supported the pro-Soviet Communist militia MPLA, led by Jose Eduardo dos Santos (President of Angola between 1979 and 2017), with weapons, equipment, and military advisers, which fought against UNITA paramilitary units, which in turn enjoyed the support of South Africa and the United States.

On the African continent, Soviet troops were also present in Ethiopia, helping the socialist regime led by President Mengistu Haile Mariam, who embroiled his country in the war for the province of Ogaden between 1977 and 1978, fighting neighbouring Somalia, while being involved in the Eritrean War of Independence, which raged in the north between 1961 and 1991. The Soviets also had a military presence in Egypt, supporting a close Soviet ally, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Thus, Egypt used Soviet equipment and weapons during the Suez Crisis in 1956 and the Six-Day War in 1967, and in the war of attrition against Israel in the Sinai Peninsula between 1967 and 1970, Soviet troops fought on the Egyptian side, especially Soviet pilots who operated MIG fighter jets.

Soviet military advisers and other military personnel were not only present on the “black continent”, but also worked in many Asian countries, where during various wars, uprisings, and armed conflicts, they tried to tip the scales in favour of pro-Soviet regimes or militant groups. In the Korean War (1950-1953), many Soviet military pilots fought on the side of North Korea, there were also many Soviet military advisers in the North Korean army and even more Soviet weapons with which the declaratively communist North Korean regime of Kim Il Sung fought against South Korea and its allies, consisting of United Nations military units under US Command.

The Soviet Union was given another opportunity to expand its influence during the Second Vietnam War (1955-1975), when the Soviets were heavily supportive of the Vietnamese communist forces. After the end of the First Vietnam War (1946-1954), Vietnam (like Korea) was divided into pro-Western South Vietnam and pro-Soviet North Vietnam, and the border between them was the 17th circle of latitude. Soon after the departure of French colonial forces from Indochina (1954), clashes broke out between the northern and southern parts of the country, which eventually led to extensive intervention by the United States and its Allies (Australia, the Philippines, South Korea, Laos, Thailand). On the other hand, the Warsaw Pact, and its Allies (China, Cuba, North Korea) also got involved in the war, sending troops and equipment en masse in support of their communist allies in North Vietnam. During the war, the Soviet Union sent thousands of pieces of artillery, cannons, tanks, light weapons, and other equipment needed to fight Vietnamese, and more than a thousand Soviet soldiers fought in the ranks of North Vietnam, and even more were active as military instructors and advisers.

Even though today’s Russia is far from the power and greatness of the former Soviet Union, it has not given up its high-flying geopolitical ambitions and military presence in various parts of the world. The best example of this is Syria, which was already a Soviet allied state and maintained good relations with Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union. When a wave of revolutions, also known as the Arab Spring, broke out in North Africa and the Middle East in 2011, it led to a bloody civil war in Syria, which unfortunately continues today and in which more than half a million people have died so far. Russia, which has had military bases in the country for decades, has strongly supported the Syrian regime with weapons, equipment and military experts since the start of the war, and in 2015 to protect its own interests in the country, along with Iran and Shiite Hezbollah also intervened militarily on the side of the regime of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad, with its forces allegedly committing a number of war crimes, the most high-profile of which were chemical weapons attacks in 2013 and 2017.

However, Russia’s military presence in “third world” countries is far from limited to Syria, but also to many other countries in Asia and Africa. In Asia, the Russian navy is present in Vietnam, where it has a naval base Cam Ranh Bay, and in addition to the disintegration of the Soviet Union with six other former Soviet republics (Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan) joined in the so-called Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), which is somewhat reminiscent of the former Warsaw Pact. Just as in the case of the Warsaw Pact where the Soviet Union had the main say in all matters, Russia has the main say in all matters in the case of the CSTO, which also has its own military units stationed in the member states to intervene, if necessary, against real threats (e.g., the Tajik civil war between 1992 and 1997) or against political opponents of the authoritarian regimes of all these countries.

Finally, I would like to mention Russia’s imperialist policy in Africa, where Russia protects its interests by supplying weapons and military equipment to authoritarian regimes, as well as by mercenary units such as the infamous Wagner Battalion, most present in Libya, where they are fighting on the side of renegade General Khalifa Haftar against the internationally recognised government of Fajez al-Sarai, and to a lesser extent their dishonest business in the Central African Republic, Mozambique, and Sudan.

Conclusion

As we have seen in the article, today’s Russia is just as militant and expansionist as the former Soviet Union, but unlike the latter, Russia no longer has an extensive network of allies and a robust economy to support the entire military apparatus. Nevertheless, Russia is not ready to give up its territorial appetites and aggressive appearances on the international stage, which can lead to news in the future about Russia’s violent repression of ethnic groups, incitement to armed conflict around the world, and crimes of Russian mercenaries and paramilitaries units in the countries of the “third world”.