By: Dr Vinko Gorenak

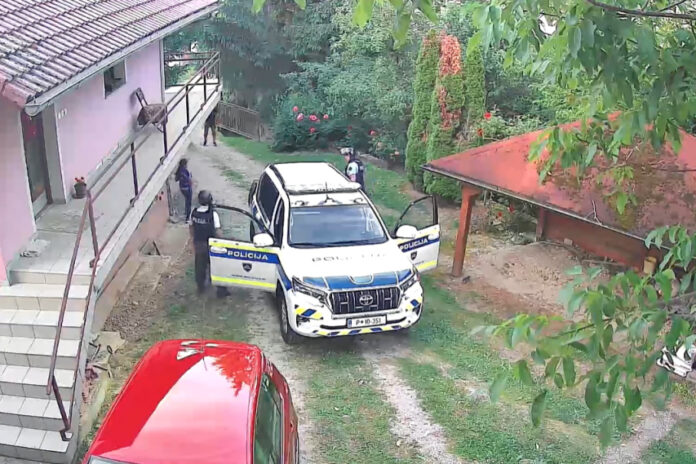

On September 30, 2025, at 6:06 AM, officers from the Department for the Investigation and Prosecution of Officials with Special Powers at the Specialised State Prosecutor’s Office rang the doorbell of Aleš Hojs’s house with a warrant for a house search.

Reason: In 2021, Aleš Hojs, then Minister of the Interior, was allegedly informed by an unknown perpetrator from the police about planned house searches in the “Kavaški Clan” case, and supposedly notified members of the clan about the searches. A bedtime story that does not withstand serious scrutiny, but I leave judgment of this claim to others. In this article, I intentionally omit the Patria case as an example of abuse by the police, prosecution, and judiciary, since most of us already know everything about it.

What is the Department for the Investigation and Prosecution of Officials with Special Powers?

It is a specialised unit within the prosecutor’s office, established during the first Janša government, partly at the initiative and request of the EU, based on the principle that police officers cannot investigate other police officers. Thus, this department was created to investigate suspected criminal offenses committed by police officers, members of SOVA (Slovenian Intelligence and Security Agency), or members of the Ministry of Defence’s intelligence service, specifically, individuals with special powers. The department is responsible for handling criminal offenses committed by officials from:

- the police,

- the military police with police powers in pre-trial procedures,

- those with police powers in pre-trial procedures deployed on foreign missions,

- the intelligence-security service of the ministry responsible for defence,

- the Slovenian Intelligence and Security Agency.

Hojs did not fall into any of these categories in 2021, so according to the letter of the law, and in my opinion, these investigators should not have been allowed to investigate him.

Abuses within the police, prosecution, or judiciary systems

Abuses occur within the police, prosecution, or judiciary systems, and often within all three. Recent history is full of demonstrable cases of illegality involving one or more of these institutions.

Naturally, a logical question arises: how is it even possible for abuses to occur within institutions that are supposed to be independent and operate solely based on the law? More on that in the conclusion of this article.

The case of Robert Fojkar – prosecutorial abuse

Prosecutor Branka Oven from Nova Gorica pursued criminal charges against Robert Fojkar for alleged paedophilia for eleven years. He was never convicted, neither at the first instance, nor at the higher court, nor at the Supreme Court. The proceedings dragged on because the prosecutor kept appealing. Eventually, the Supreme Court of the Republic of Slovenia issued a final and binding decision that Robert Fojkar was not guilty of the alleged crime, as he was not present at the scene. The court also reprimanded Prosecutor Oven – who later became head of the Nova Gorica prosecutor’s office – stating that she abused her position in the Fojkar case and filed appeals without justification. A demonstrable abuse of prosecutorial authority, therefore.

The case of Andrej Magajna – police abuse

You have probably forgotten. Andrej Magajna, a Christian socialist, was around 2010 a member of parliament for the Social Democrats. He strongly opposed the RTV law. Just days later, he was subjected to a house search. He was accused of paedophilia. But lo and behold, the police lost the hard drive from his computer, and shortly afterward, they lost the copy of the hard drive as well. Magajna was acquitted of all charges, yet no one from the police ever apologised. A clear case of police abuse.

The case of Franc Kangler – police-prosecutorial abuse

Against the MP from the SLS and mayor of Maribor, 24 criminal complaints were filed. All search warrants at Kangler’s residence were signed by the same investigating judge – the notorious Janez Žirovnik, former deputy head of SOVA. Kangler, as an MP, was also an overseer of SOVA. Kangler was never convicted in any case, yet Žirovnik was promoted to Supreme Court judge. A clear abuse by the police, prosecution, and the investigating judge.

The case of Vrskarsić – pure judicial abuse

You have probably forgotten. In 2012, the court decided to auction off the house of Vasko Vrskarsić from Litija because he had not paid around 250 euros in municipal fees. The house was sold for 80,000 euros, 250 euros were transferred to the municipal company, and the rest to him. The European Court of Human Rights ruled that the Slovenian judiciary’s decision was disproportionate and awarded Vrskarsić an additional 80,000 euros in compensation, paid by taxpayers. A clear case of judicial abuse.

The case of Andrej Šircelj – abuse by police, prosecution, and investigating judge

On December 15, 2015, around 8:30 AM, I arrived at the National Assembly in my parliamentary office. My neighbour was Andrej Šircelj, also an SDS MP. Between our offices stood a young man like a silent guard, whom I immediately recognised as a police officer. I asked if he needed anything, but he did not respond. A house search followed in Šircelj’s office and at the SDS headquarters. The warrant stated that police could seize the SDS server, which contained around 30,000 email addresses of SDS members. This meant police could have seized all email communications of SDS members. A blatant abuse of the law. Of course, we did not give them those data, but we did provide all communications related to Šircelj. The media reported sensationally on the search, but 10 years have passed and no police, prosecutorial, or judicial proceedings were ever initiated against Šircelj. No apology was ever made.

When police, prosecution, and judiciary abuse the law, and a mobile operator stops them

Around 2010, unknown individuals broke into a facility near Postojna. Police worked hard to identify the perpetrator. Eventually, they requested from a mobile operator the phone numbers of everyone who had communicated via the nearest cell tower during the time of the break-in. This is illegal, they can only request whether a specific number was connected to the tower at the critical time. The police requested data without legal grounds. The prosecution approved the request, and, believe it or not, the investigating judge issued an order for the operator to hand over all phone numbers that had communicated via that tower. The judge acted unlawfully. But the operator’s legal department (I will not name the company) informed the judge that there was no legal basis for such a request. The judge could have penalised the responsible person at the operator and ordered them to comply. None of that happened. The judge simply forwarded the operator’s response to the police, and that was it. A shocking and outrageous abuse by the police, prosecution, and judiciary.

The case of Anton Štihec, Zmago Jelinčič, and Srečko Prijatelj – abuse by police and prosecution

More than a decade ago, the public was stirred by the infamous “corruption affair” involving numerous house searches by criminal investigators. Suspects included MP Zmago Jelinčič, his SNS party colleague Srečko Prijatelj, Agriculture Minister Milan Pogačnik, and Murska Sobota mayor Anton Štihec. Jelinčič was dramatically brought before cameras to the National Assembly, where a search was conducted in his office. Prijatelj was “caught” in Sežana allegedly accepting a bribe. Štihec, who was not even a suspect, the municipality he led was under investigation, was detained for several hours by criminal investigators led by Aleksander Jevšek, now a minister in Golob’s government and then head of Slovenian criminal police. Jevšek later won elections and became mayor of Murska Sobota. The court’s epilogue: none of the accused were convicted of any “serious crimes.” But the goal was achieved – discrediting the individuals involved.

Why are abuses even possible?

The reason lies in the supposed professionalism and independence of these institutions, which often go unchecked, especially the prosecutorial organisation. While police decisions are reviewed by the judiciary, and court decisions by the Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights, prosecutorial decisions to dismiss criminal complaints are reviewed by no one. They answer only to God and the blue sky. The answer to this question is nearly impossible. But one thing is clear: while police and prosecutors are part of the executive branch and aim to convict alleged offenders, the judiciary is in a completely different position. According to the constitution and law, the judiciary is an independent branch of government and should act accordingly, lawfully assessing the actions of police and prosecutors. Unfortunately, this is often not the case. Worse still, judges who assist in abuses by police and prosecutors seem to advance more quickly, which is utterly unacceptable.