By: Peter Jančič (Spletni časopis)

I am in Germany as you read this column. Today’s elections there will have a significant impact on the future of Europe and on us.

During the terrorist attacks by foreigners – one of which occurred in nearby Villach – these elections and the future will be marked by the fact that the new U.S. president, Donald Trump, has allowed Vladimir Putin to return from the status of an aggressor and occupier, who cannot be trusted, to that of a dialogue partner of a superpower. Trump also insulted the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, calling him an unelected dictator who attacked Russia and failed to achieve peace with Putin in recent years. Trump even assessed that Zelensky was unnecessary for making peace with Putin.

This is quite an earthquake for Europe and for Germany, especially since Trump, during his previous term, had warned European countries to take better care of their security. However, many European countries, except for Poland, largely ignored this advice – even after Putin’s annexation of Crimea, the silent occupation of parts of eastern Ukraine, and the full-scale invasion that shook Europe’s stability and triggered a wave of refugees.

Putin suffered a setback when attempting to capture Kyiv due to the resistance of Ukrainians, with Zelensky refusing an offer to flee and stating that he needed ammunition, not a ride. Ukraine received weapons, but often too late, in insufficient quantities, and sometimes outdated.

Therefore, Trump’s recent insults toward Zelensky are an even greater shock – especially when Trump, after Zelensky accused him of falling for Russian disinformation, responded by calling Zelensky an average comedian who would soon lose his country if things continued this way. Zelensky already experienced Trump’s potential danger last year when a prolonged blockade of U.S. aid by Trump’s supporters in Congress led to Ukrainian defeats on the front line due to a shortage of ammunition. However, Trump eventually changed his mind, and the situation improved.

Without this reversal, Putin would have occupied even more territory.

It remains unclear what exactly Trump was trying to achieve when, after starting negotiations with the Russians, he suddenly adopted the Kremlin’s stance that Ukraine had attacked Russia and not the other way around. This prompted a British tabloid to depict Trump as a poodle on Putin’s leash on its front page. Perhaps Trump was simply enraged that a politician whose country has been mercilessly destroyed by Russia for three years dared to criticise him – especially after Zelensky refused to sign a deal offering Trump half of Ukraine’s mineral resources in exchange for help. Zelensky stood up to Putin when it was truly dangerous, and for three years, he has been challenging a more powerful force. Now, he is also standing up to Trump – which is dangerous again.

They might get rid of him together.

Negotiations over mineral resources are ongoing, and it seems that, after initial ultimatums, the United States has somewhat softened its stance.

The stakes are high for Ukraine and Zelensky. Without allies, they could disappear from the face of history. This is Putin’s goal: to persuade Trump that Ukraine should relinquish the territories Russia has additionally occupied over the past three years – and perhaps a bit more – for the sake of “peace.” This would allow Trump to focus on issues that are more important for the United States, such as China.

Putin’s assault on Ukraine is not an anomaly. For a century, Moscow has been known for its imperialism and brutal attempts to conquer neighbouring countries. Sometimes, these attempts fail. Russia’s expansionist ambitions also extend toward Europe, where some EU countries have recently begun shifting their support from Ukraine to Putin – though, for now, these are less influential nations. Most notably, Hungary and Slovakia’s leadership are leaning in this direction. With the rise of the AfD, Germany could follow suit. Even Slovenia’s government shows partial alignment: the ruling party, Levica, advocates for halting all military aid to Ukraine. Putin is demanding the same from European countries in his negotiations with the United States. Prime Minister Golob seems to be drifting toward Moscow’s orbit, alongside influential figures such as Milan Kučan and Zmago Jelinčič. Historically, Russia has relied on support from both the far left and the far right. A former ambassador described the consequences of Europe initially excluding Slovenia from talks as follows:

“Now things are getting serious, and in my opinion, they’re acting wisely. There’s no point wasting time on a country that can’t even find the money for its own soldiers – lost somewhere in the galaxy of peacekeeping NGOs.”

Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico declared that Slovakia would no longer send a single bullet. As for Golob, I have not observed such a statement. Golob’s supporters might argue that Slovenia’s prime minister is merely aligning with Trump’s forthcoming stance toward Moscow – before Trump has even taken action. However, that is not accurate. Trump has not halted military aid to Ukraine. Still, his unpredictability makes it impossible to predict his next move. It is unclear whether he will align with Putin, to whom Tanja Fajon had previously suggested sending former Prime Minister Janez Janša as a mediator. Janša, however, took a bold step: when Russian troops were advancing toward Kyiv, he travelled to Ukraine with representatives from Poland and the Czech Republic – the first European leaders to show their support for Ukraine’s resistance.

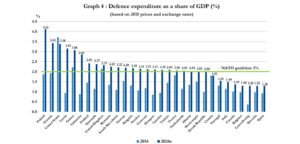

Golob’s government, according to objective data, aligns more closely with Putin’s interests than with those of the West when it comes to defence. Units that should already be contributing to Europe’s security do not exist – not even on paper. The government has only recently begun ordering armoured vehicles for these non-existent forces, after cancelling such orders three times. Nations that fail to keep their promises lose credibility. In times of war, they become more dangerous than enemies. The data revealing how poorly our country ensures its security is as follows

Last year, only Spain spent less on defence in the EU than Slovenia. Spain’s government, like Golob’s, made headlines by recognising Palestine after Hamas and Hezbollah – both backed by Iran – launched attacks against Israel. For Putin, this war ended poorly: with most of Russia’s military focus on Ukraine, Russia had to retreat from Syria when the situation there became complicated. Syria had been crucial for supplying Hamas and Hezbollah with support from both Iran and Russia.

This recognition was not about the interests of the West or NATO – perhaps it aligned more with the interests of non-aligned friends or even Moscow.

Overall, it seems that today’s politicians are steering the country as if it were a non-aligned socialist Yugoslavia after the death of Josip Broz Tito – only closer to Moscow than Tito ever was. Tito feared the Kremlin, and for good reason – he was no fool. Yet, some Slovenian politicians today seem almost like part of Putin’s broader team in the EU. Take, for example, the behind-the-scenes powerbroker of the current government, Zoran Janković – a close friend of Serbia’s Aleksandar Vučić.

This is happening at a time when tensions could flare up again in the Balkans. After all, if Russia is allowed to seize its neighbours’ territory by force, what is stopping Serbia from doing the same? They could claim an attack from Croatia and justify military intervention to protect their minority population in Knin or Kosovo – just as Russia did in Ukraine.

There are several reasons why Slovenian politicians lean toward Russia. Slovenia’s steel industry, a cornerstone of Yugoslavia’s military sector, was sold decades ago by Janez Janša’s first government to a Russian businessman. The acquisition of Janković’s Mercator – sold cheaply by Alenka Bratušek to Croatia’s failing Agrokor, owned by Ivica Todorić – was financed by Russian banks. Slovenia’s pharmaceutical companies have factories and markets in Russia, and in the energy sector, both Janković and Golob rely on Russian gas and Chinese solar panels rather than Western nuclear alternatives, which produce less greenhouse gas emissions and have helped secure Slovenia’s energy supply in recent years. Nuclear power has even personally benefited Golob, as GEN-I primarily traded electricity from NEK (the Krško Nuclear Power Plant).

So far, the outcome in Ukraine has been unfavourable for Europe – much like during the wars in Yugoslavia, where the bloodshed in Bosnia and Kosovo only ended after U.S. military intervention. Economically, Russia is no superpower. Last year, the combined GDP of EU countries was $17 trillion, that of the U.S. was $28 trillion, while Russia’s GDP stood at just $2 trillion – lower than Italy’s. Europe (excluding Ukraine) also surpasses Russia in population, with 448 million people compared to Russia’s 143 million.

Russia has not broken in Ukraine because Putin has proven to be a more capable leader than many European politicians – leaders who often prefer to shift the costs of their own security onto someone else. Especially in Slovenia.

At the same time, Europe has felt the consequences – millions of refugees from Ukrainian regions occupied and devastated by Russian forces, where ethnic cleansing was carried out. The United States is far less affected by this. Another consequence could be the loss of Ukraine’s energy and economic potential and an increase in Russia’s capacity for further territorial conquests.

Compared to this, Gaza is a minor issue.

However, Putin also underestimated Ukraine. His calculation was that occupying it would be easy – just as the Soviet Union once did with Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and others.

But Ukrainians resisted him, much like the Finns once resisted Stalin or the Chechens resisted Putin. After encountering difficulties with the Chechens, Putin negotiated ceasefires to resume the war with even greater force. He also agreed to similar deals with Ukraine – such as after annexing Crimea – only to later break those promises. Three years ago, he solemnly assured the world that he would not invade again, even as his troops were already stationed at Ukraine’s borders. “It is just military exercises,” we were told.

Of course, he attacked – and blamed Ukraine and NATO for the invasion.

Now, Trump is echoing Moscow’s propaganda, angered by Zelensky.

Trump’s running mate, J.D. Vance – who not long ago lectured European leaders on the importance of free speech – has completely changed his stance. He now insists that Trump must not be criticised and has warned of consequences for the “ungrateful” Zelensky.

If Trump takes a shortcut toward Moscow to secure peace, the consequences for Europe could be catastrophic – potentially paving the way for another war. Moscow could accuse yet another neighbour of attacking them, just as Putin’s “little green men” with tanks might suddenly appear in Transnistria or Poland near Kaliningrad.

Since Russia’s invasion, Europe has sent over €130 billion in aid to Ukraine, while the United States has provided more than €110 billion. But it is essential to be cautious with these figures – politicians often inflate them, including investments in their own militaries and industries, or count outdated equipment sent to Ukraine that would otherwise have been scrapped. For example, Slovenia donated its outdated Soviet-era tanks, inherited from Yugoslavia and only minimally upgraded. But Slovenia did not replace these donations with newer armoured vehicles. The government disregards national security – even though, under the previous regime, we were taught to prepare as if war could break out tomorrow. The numbers reflect this neglect.

That is what the numbers show.

The consequences of Trump’s train toward Moscow are unpredictable. But one thing is certain: the impact will be significant.

That is why tensions are high.

Also in Germany, where today’s elections are partly about this very issue.