By: C. R.

We are publishing a new open letter from Dr Jože Dežman regarding the return of the statue of Josip Broz Tito to the Brdo Park.

Directorate for Cultural Heritage

Slovenian Museum Society

Community of Museums of Slovenia

ICOM Slovenia

Museum of Contemporary and Modern History of Slovenia

Board and Expert Council of the Museum of Contemporary and Modern History of Slovenia

Public Economic Institution Brdo

Information Commissioner

Subject: Can the Ministry of Culture or the Government of the Republic of Slovenia hand over inventoried immovable cultural heritage to institutions that are unable to properly care for it, and why are they hiding their documents about it?

In light of the unsubstantiated claims found both in the documents of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia, and particularly in the statements made by the Minister of Culture at the MNZS outdoor depot in the Park of Military History in Pivka, I would like to present some basic facts.

The collection of revolutionary court art from Vila Bled has not received professional treatment or proper care. Part of the collection remained at Vila Bled (in the orangery, and probably other items, many of which have been lost or given to other owners). A large part of the collection was later moved to the park at Brdo and, by the end of the millennium, placed in a remote location near the living fence by the racetrack. Two sculptures had already been moved before the dissolution of Yugoslavia to the then defence training centre in Poljče.

In 2000, a copy of Augustinčič’s statue of Josip Broz was added to the collection. This statue, part of the cult of personality, was initially placed in front of the exhibition centre for the 7th Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in 1958. It was later positioned in front of the Museum of the People’s Revolution. The statue was removed during the museum’s renovation after 1990, which did not provoke any public outrage or protests. Around 2000, the statue was relocated to the revolutionary collection at Brdo.

Additionally, a statue of a courier was added to the collection, most likely due to its relevance within the system of preserving and developing revolutionary traditions.

The statues at Brdo were neglected, poorly presented, and rarely visited. JGZ Brdo registered them as consumable materials with a book value of zero. The statues in Poljče were not even inventoried. It is likely that the heritage at Vila Bled is also inadequately inventoried.

These facts provide more than enough reason for my proposal to consolidate the collection where feasible, transfer it to the management of the MNZS (as the appropriate heritage institution), and ensure its proper presentation.

The statues from Brdo were transferred to the MNZS through a contract between MNZS and JGZ.

The space for the outdoor depot at the Park of Military History was secured through a contract with the Municipality of Pivka.

The installation of the collection within the framework of the national museum depots in Pivka was included in the MNZS’s work programme for 2022. Furthermore, the condition of the sculptures was assessed by the Restoration Centre, and they initiated a pioneering project to preserve bronze sculptures. The transfer to Pivka was carried out according to the guidelines of the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage (ZVKD).

The setup was realised as the MNZS Outdoor Depot. Funding for the project was approved by the Ministry of Culture and disbursed while Asta Vrečko was already the Minister of Culture. The MNZS reports for 2022 were duly accepted. If there were any issues, such acceptance likely would not have occurred, right?

Asta Vrečko and the Government of the Republic of Slovenia keep reiterating that there were alleged irregularities, which is why they annulled the contract between MNZS and JGZ Brdo. If such irregularities existed, they share responsibility for them.

I have received no response to questions regarding the legal basis for the contract’s annulment, who made the decision to annul the contract, or who decided to return the sculptures from MNZS to JGZ Brdo. There is also no clarity on what will happen to the two sculptures from Poljče.

These documents should be made public, as this is a significant issue.

In the attached document, I point out that in 1986, the Socialist Republic of Slovenia transferred a multitude of state-owned artworks to the National Gallery’s management. This included artworks from Brdo. The National Gallery manages them with considerable freedom.

However, the National Gallery did not take over the revolutionary art. Moreover, Tito’s court collection has not received particular attention from art historians or heritage custodians. Even the artists themselves did not boast about these works. Thus, the dismemberment and removal of this collection from more highly valued works reflect a clear assessment of these pieces as not particularly esteemed.

The initiative for the National Gallery to also take responsibility for this collection was rejected because they lacked the necessary conditions to manage even the other works from this fund.

Therefore, MNZS took over nine sculptures from Brdo and two from Poljče. The sculptures were inventoried by MNZS, making them part of the protected movable heritage.

If the Ministry of Culture (MK) wanted, it could have assigned MNZS to set up a new installation at Brdo.

But no, MK or the Government of Slovenia, or perhaps even a third party, instructed MNZS to hand over the heritage to a manager who had already proven to be a poor custodian of it. There are no guarantees that JGZ Brdo would be able to manage this collection any better than before.

Hence, I urge the Slovenian Museums Association, the Museum Society, and ICOM Slovenia to request the documentation on the procedures led by MK, by which heritage is being transferred from an authorised museum to an institution that has demonstrably been unable to manage immovable cultural heritage.

I ask you to request from MK an explanation of why the National Gallery is considered an appropriate manager of immovable heritage at Brdo, but MNZS is not.

And I ask you to, after thorough discussion, adopt appropriate recommendations on how to act in such cases of arbitrary governmental decisions and ideological bias in the future.

Let me note that much of what I am mentioning here was published in the magazine SLO Časi, kraji, ljudje in September 2023 and in this year’s sixth report of the Government Commission of the Republic of Slovenia for resolving the issues of concealed graves.

Looking forward to your response.

Best regards,

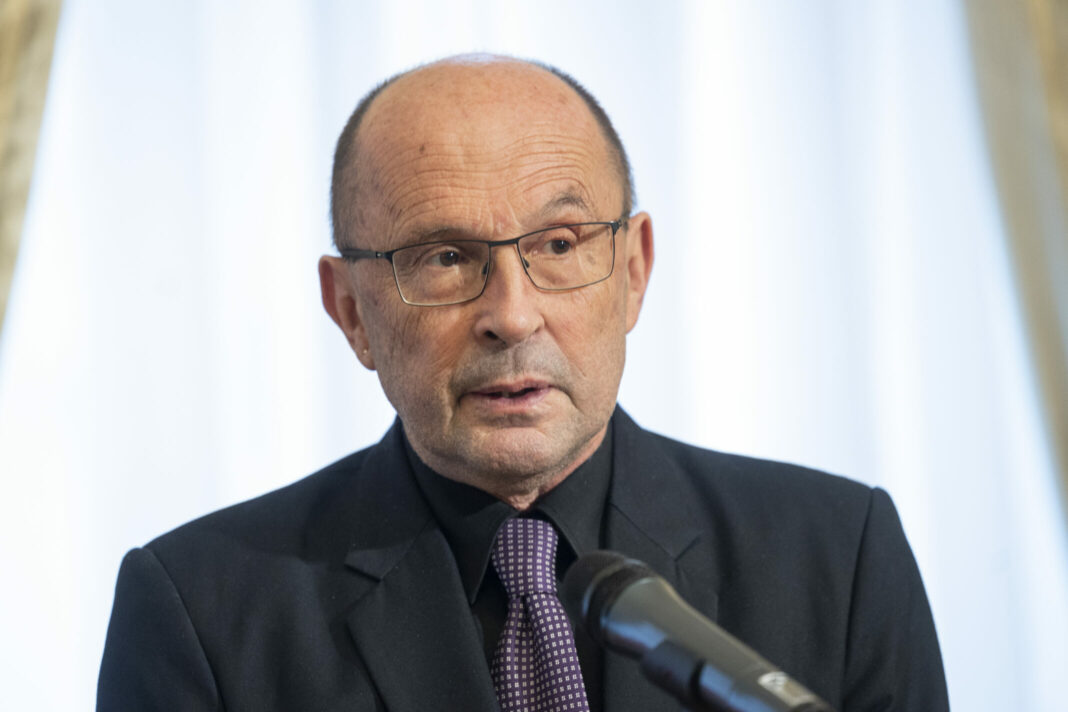

Dr Jože Dežman

Attachment:

1986 – The Executive Council and the National Gallery

On March 6th, 1986, Janez Zajc, the General Secretary of the Executive Council of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia (IS), and Anica Cevc, Director of the National Gallery (NG) in Ljubljana, signed a contract regulating the mutual relations regarding the transfer of management rights over artworks. NG took over the management of more than a thousand artworks that were owned by the Executive Council.

NG also took over the management of significant artworks at Brdo Castle, but not the sculptures. It is not known why NG did not take over the sculptures. When MNZS inquired with NG if they would take over the collection from Vila Bled, the answer was negative, as they already lacked sufficient resources for managing the above-mentioned artworks.

In managing the relations between MNZS and JGZ Brdo, we followed the guidelines outlined on March 6th, 1986, in the Executive Council’s decision regarding the transfer of management of artworks to the National Gallery: “The artworks located in the premises of the Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia will remain there unless, following a professional evaluation in the interest of cultural heritage protection and its broader accessibility to the public, the National Gallery in Ljubljana decides to redistribute them elsewhere. In such a case, the Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia reserves the right to have the National Gallery in Ljubljana replace the artwork with another, suitable for the environment.” It is also expected that the authorities and the gallery would agree on a “multi-year programme of restoration works on art pieces and their execution in individual years”.

Most of the maintenance is not carried out at an appropriate professional level. There are more records like this one about two high school girls who “listened to their grandmother, the president of the Tolmin city organisation of the WWII Veterans Association, who complained about the high costs of restoring the monument dedicated to the victims of World War II, and they offered to do what they could. Every day, they spent a few hours at the Tolmin cemetery restoring the inscription on the monument to the fallen in the National Liberation War (NOB) in Tolmin and the surrounding area. The monument bears around a hundred names, engraved on marble plaques that had faded over time. Their work was slow and time-consuming, as the plaques first had to be cleaned, and then the engravings carefully and meticulously filled with special markers resistant to atmospheric conditions. After a week, they completed the work and proudly posed for a photo in front of their creation.”

The movement of artworks in accordance with these principles has happened and continues to happen. For example, the following paintings were moved from Brdo Castle to the permanent exhibition of the National Gallery:

- Matteo Ghidoni: The Life of the Poor, around 1680 (?)

- “Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia: furnishing of Brdo Castle near Kranj; 1986 The Executive Council transferred management to the National Gallery.”

- “Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, hung in the hallway of Brdo Castle near Kranj; 1986 The Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia transferred management to the National Gallery.”

- Matteo Ghidoni: Robbers’ Refuge, 17th

- “Unknown author: Lady in the Square, around 1650.” “Provenance: unknown. After the second war, located in Brdo Castle near Kranj; in 1986, the Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia transferred it to the National Gallery.”

- Friedrich Gauermann: Wild Rooster, mid-19th

- “Provenance: unknown. After the second war, it hung in the foyer of Brdo Castle near Kranj; in 1986, the Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia transferred it to the National Gallery.”

- Pietro Liberi: Gyges and Nyssia on the night of the murder of her husband Candaules (?).

“At an unknown time, the painting was removed from the National Gallery and hung in the hallway of Marshal Tito’s residence at Brdo Castle near Kranj. In 1986, the Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia handed over all paintings and sculptures from this building to the National Gallery. This old gallery property was among the items found.”

In a historical context, the contract between the Executive Council of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia (IS SRS) and the National Gallery (NG) is marked as the second milestone after the abolition of the Federal Collection Centre (FZC), which “was authorised by the government to collect and safeguard cultural-historical objects throughout Slovenia and gather them in Ljubljana for a future central Slovenian museum. The first milestone was the dissolution of the FZC, even though the centre was not officially disbanded, and the sale, loan, or lending of acquired works; this occurred between 1947 and 1948. Then followed a long period of silence until 1986, when the Executive Council of the Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia adopted a resolution transferring the right to manage artworks located in its premises, in the premises of other bodies and organisations, and even those artworks temporarily in the possession of individuals, to the National Gallery in Ljubljana. The Executive Council and the National Gallery also signed a contract regulating the mutual relations regarding the transfer of this right to manage artworks. In 1997, Dr Andrej Smrekar, then director of the National Gallery, again drew attention to the unresolved issue of stolen paintings. In April of that year, the National Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia was formally notified to finally begin addressing the issue of the formal legal status of the heritage from the FZC, as the matter is complicated and concerns ownership status, property rights, and the national cultural-historical significance of these items.”

It is somewhat ironic that, during the transition period, similar dilemmas arose with the statues from Villa Bled and many similar sculptural monuments across Slovenia, dedicated to the partisan movement and the dictatorship of the proletariat.

When the National Museum of Contemporary History (MNZS) and the public institution JGZ Brdo concluded an agreement on the long-term loan of the statues, we recorded: “The user may use the artworks for the following purposes:

- exhibition to museum visitors,

- restoration,

- professional custodianship.”

This principle was respected in the further development of the project.

Villa Bled

The statues that were later placed in Villa Bled were created between 1947 and 1948. Vanja Radauš’s Bombaš was exhibited in 1947 at the Yugoslav exhibition in Ljubljana. At the Slovenian exhibition in 1948 at the Museum of Modern Art, the works from this collection included The Partisan Family by Božo Pengov, Udarnik by Tine Kos, and The Lumberjack by Tine Kos.

The exhibition also featured several other statues thematically related to the new era. Bombaš and Partisan in Charge were smaller statues, while the larger ones included The Dying Hostage, Youthful Sower, and Žanjica.

A new form of sculpture was emerging, meant to celebrate the partisan struggle and the land of the victorious dictatorship of the proletariat.

The artists chosen for Villa Bled were later the standard-bearers of the new style. If we speculate that Ivan Maček was behind these decisions, then it may be in his shadow that Lojze Gostiša took his first steps in shaping the culture of the new class.

According to Gojko Zupan’s findings, The Lumberjack and Udarnik were cast for Brdo.

According to available photographs, the statues were initially placed inside Villa Bled (Bombašica by Karlo Putrih, Partisan by Zdenko Kalin, and Leading the Brigade by Boris Kalin) or on its terrace (Bombaš by Vanja Radauš). In the garden stood The Partisan Family by Božo Pengov. Given their original placement, referring to these statues as garden sculptures is more of a justification for the state of affairs that only occurred when part of the collection was installed at Brdo.

At Brdo, the statues were initially placed on brick pedestals throughout the park. Photographs of the statues at Brdo are rare, and it does not seem that Broz or high-ranking visitors paid much attention to them.

If the first placement at Brdo was likely realised with the consent of Josip Broz, some suggest that the later relocation of part of the collection with partisan-proletarian themes to a hedge-lined area reflected ideological doubts about the collection. However, this was during the left-leaning governments of Janez Drnovšek, and it seems that no deeper ideological motives were at play beyond pragmatic considerations.

The two statues in Poljče were placed without any landscaping effort – The Partisan Family on a narrow lawn in front of the building, and Bombaš next to a garage canopy.

Neither art history nor monument protection was documented in these decisions to relocate the statues, and it is not known if any official documents were produced during these placements.

In May 2015, Mateja Breščak and Gojko Zupan wrote: “The temporary nature of the sculpture collection placement is evident, confirming that the statues were made for outdoor spaces, though not for larger squares, but more for adorning smaller courtyards or garden spaces. These are pathetic but not particularly monumental statues. We assume they were conceived for the Villa Bled Garden, as supported by some documents. The collection, due to its rarity, deserves greater attention and care. In Slovenia, we have no comparable collection of full-figure statues of workers and partisans from the first half of the 20th century in outdoor settings.”

However, the statues Breščak and Zupan analysed are not all that need to be considered for a comprehensive evaluation of the sculptural heritage of Villa Bled.

They analysed: B. Kalin’s Zastavonoše (Leading the Brigade?), K. Putrih’s Bombašica, Z. Kalin’s Partisan, K. Putrih’s Worker with a Compressor (Miner?), T. Kos’s The Lumberjack and Udarnik, and Z. Kalin’s Žanjica. For these two statues, Breščak and Zupan suggested that “the statue can remain at its current location near the castle or be included in the group of workers (Worker with a Compressor, The Lumberjack, Udarnik)”.

They proposed separate treatment for:

- S. Keržič: Kurirček (Landscape architects can find a long-term space for the statue on the narrower part of the estate.)

- Augustinčić: Tito (We suggest finding a new location for the statue within the estate, separate from the group of worker statues. It could be moved near one of the cottages on or near Račji Otok.)

- Putrih: The Nude (This is the only preserved outdoor decoration from the Karađorđević era. We suggest considering a new, simple pedestal and perhaps reconstructing the jug.)

The open question is why Breščak and Zupan did not include in their analysis the two statues from Poljče: The Partisan Family and Bombaš.

Also unresolved is how to handle and preserve the remaining revolutionary art heritage in Villa Bled.

Take, for example, the florist shop. The building, which is falling apart, is in urgent need of renovation. Should the reliefs by Karlo Putrih Agriculture and Construction be preserved? Inside the florist shop are additional reliefs based on motifs by Đorđe Andrejević Kun (The Partisan Worker and Peasant; The Partisan Family, Partisan Uncle Vule, The Little Partisan Courier Jovica). What should be done with them?

Breščak and Zupan, who highly valued the Brdo portion of the Villa Bled collection, did not comment on how Špelca Čopič, who studied Slovenian sculpture up to the mid-20th century, did not mention these statues at all.

Sculptors and art historians have viewed this sculptural direction more as a detour than a developmental achievement.

Sculptors did not boast about the partisan and proletarian figures created for Villa Bled. In the 1956 monograph on Zdenko Kalin, Žanjica is listed as being at “Villa Bled,” but there is no mention of the Partisan from Villa Bled. The Little Shepherd is listed as being owned by the Museum of Modern Art, and in a photograph from the 1969 reception of Italian President Giuseppe Saragat at Villa Bled, The Little Shepherd can be seen in the background. It was likely brought from Brdo for this occasion. Katarina Mohar, who dates this photograph to 1951, places The Little Shepherd at Villa Bled.

In the 1958 monograph on Boris Kalin, Morning II, a nude, is listed under “Villa Bled”, but the group Zastavonoše (Leading the Brigade) from Villa Bled is not mentioned.

We do not have exact dates for when the statues were relocated from Villa Bled. Mohar states that The Partisan Family and Bombaš were moved to Polje in 2015, but we find both statues photographed in Poljče on the cover of the first issue of Slovenske Novice on May 14th, 1990.

From the above, it follows that the sculptural heritage of Villa Bled has not yet been properly evaluated. If new placement ideas are emerging, it is necessary to consider the whole collection, not just the part that ended up at Brdo.

Critics opposing the arrangement of the open-air depot at MNZS in PVZ in Pivka emphasised that the collection was “uprooted from its context”.

However, considering the above, we can only say that the collection of Villa Bled was indeed “uprooted from its context”. But this happened decades ago, at a time when art history and heritage preservation were not particularly interested in the “uprooted” collection.

Before making any further decisions, it is necessary to conduct thorough research and respect the established facts.